Reuben Kadish, above, in his Manhattan studio in 1985. Photo: Regina Cherry

War is a terrible thing. Walt Whitman knew it, as did Ernest Hemingway. So did Reuben Kadish (1913-1992), a talented painter and friend of Jackson Pollock who found himself more or less unable, or unwilling, to paint following a stint as an Army artist in India and Burma during World War II. He re-emerged in the late 1950’s as a sculptor, working mostly in terra cotta, with which he fashioned expressionistic forms that reflect feelings of alienation and conflict.

”Reuben Kadish: Metamorphosis” at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center pulls together a selection of the artist’s sculptures, prints, drawings and paintings spanning the 1940’s to the 1980’s. Styled as a main-course survey of the artist’s career, it’s more of a tasting menu, with exhibits drawn mostly from the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation in New York City. But it’s worth seeing, if only to reacquaint yourself with the talents of this charismatic but troubled artist.

Kadish had a hankering for lefty social and political issues. In the 1930’s, he worked in Los Angeles as an assistant to the Mexican muralist and Communist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Later, he, Philip Guston and Sande Pollock (Jackson’s older brother) painted their own socialist-realist mural in the city. Mr. Siqueiros was so impressed that he invited them to Mexico to paint a mural. Titled ”Struggle Against War and Fascism,” it’s an overblown, Daliesque riff on the Sistine ceiling.

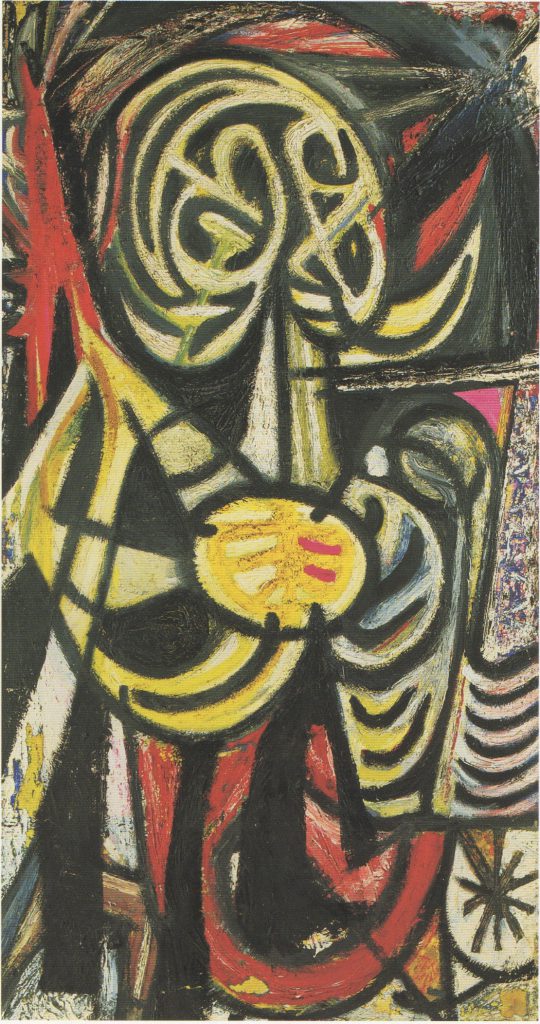

untitled, oil on canvas, 40×21, c. 1945

The war changed everything, as two wartime sketches in the present exhibition suggest. Gone is the political fervor of the murals, with their muscular, saintly worker-heroes, replaced by sharply linear, dead-eyed drones occupying devastated landscapes seething with misery. In one of these drawings we see a mound of skeletal corpses floating down a river, in the other, malnourished, naked figures sitting around grinning stupidly like mental patients. It’s all very brutal and grim.

Kadish was a wonderful draftsman, and it’s a pity more of his drawings were not included in the exhibition. In addition to an intangible graphic intensity, they reveal a somewhat unique ability to capture startling images of misery and suffering — not in a sentimental or sloppy way but with cold detachment and reality. Was this his way of dealing with it all? I don’t know, but wherever they are I would like to see a larger sampling of Kadish’s war drawings.

Returning to the United States, Kadish spent a couple of years in New York, where he painted the three untitled works from the mid-1940’s that are included here. They remind you a little of the churning, symbolic, quasi-abstractions that Pollock turned out in the early and mid-1940’s. The skeletal corpses and emaciated figures are still here, this time boxed into confined, airless spaces that look like cells, coffins or tombs. Particularly oppressive are ”Untitled” (ca. 1945) and ”Untitled” (mid-1940’s), neither of which you’d want anywhere near your kids.

Untitled (to_vincent), color monotype, 22×30, 1987

And then he moved with his young family to a ramshackle dairy farm outside Vernon, N.J., where, after almost a decade in retreat from art, he began to make sculpture. His first works were squat, crudely fashioned figures in clay, the artist ”carving directly into the pliable material with the sharpened point of a rib from a pig he had slaughtered for the family table,” the art critic Judd Tully writes melodramatically in his essay for the catalog. Later, Kadish began casting in bronze and making larger-scale pieces modeled loosely on Indian architecture and carved stone sculpture.

Head, terra cotta, 16x16x14, 1962

Although not viewed at their best in this busy, household setting, each of the half dozen sculptures here deserves careful attention. For instance, note the raw dynamism of ”Untitled (seated woman)” (ca.1970), in which a female figure crouches awkwardly in a rocky niche, or the painful interiority of ”Cocoon III” (1977), an inert, legless blob crisscrossed with sharp, deep lacerations. This is powerful stuff.

The exhibition also includes ”Gregor” (1965), an aggressive part-human, part-bug terra cotta yearling named for the character in Franz Kafka’s ”Metamorphosis.” Cradled in a dumpy wooden bed, this nasty little nipper with its pincer-like fingers and flattened feet thrashes about on its roachlike back in an effort to spin right side up. It is not often you find such chutzpah, black whimsy and downright nervy abandon in 1960’s sculpture.