Reuben Kadish and Philip Goldstein (Guston) in 1935 at the City of Hope mural in Duarte, California 1935.

The City of Hope will unveil an astonishing sight next Sunday at the public opening of its new visitors center. Those who enter the refurbished, 70-year-old Spanish Revival building in Duarte will encounter an ambitiously conceived, meticulously executed mural that depicts a sweeping progression of human life–from pudgy toddlers to ravaged elders. Inspired in part by Luca Signorelli’s fresco series painted around 1499-1504 at the Orvieto Cathedral in Italy, the mural has a cast of nude and draped characters painted in a mannerist style and staged in a Renaissance space. Harking back to a time when art was expected to portray heroic themes and figure drawing was a required skill for artists, the mural might not be so surprising at a WPA-vintage U.S. post office, but it’s about the last thing one might expect to find at a Southern California medical center.

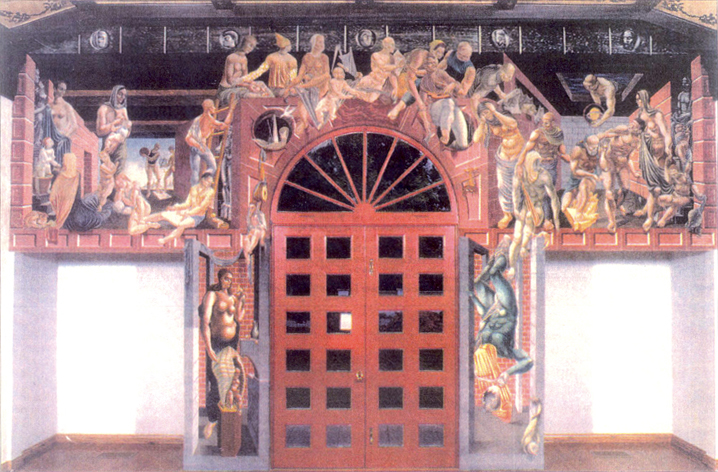

The T-shaped painting depicts more than 30 figures in an illusionistic architectural framework that reaches from floor to ceiling, spans the upper half of one interior wall and wraps around an arched doorway. Scenes on the left side portray the vigor and promise of youth; figures on the right epitomize decline and disappointment. Bridging the door and linking the two sections is an intertwined figure group representing the arts. The work is dated August 1935 to July 1936 and signed by Reuben Kadish and Phillip Goldstein.

Who?

LIfe Story: The T-shaped mural by Philip Guston and Reuben Kadish at the City of Hope depicts more than 30 figures and a sweeping progression of life.

The mural would be captivating even if it were only what meets the eye: a masterful interpretation of a big idea by two obscure artists. But–unbeknown to all but a few art historians and insiders at the City of Hope National Medical Center and Beckman Research Institute–the artwork is actually a fascinating footnote of local history because it’s a rare, early work by an artist who rose to prominence in New York, after changing his style and personal identity.

As it turns out, Goldstein is none other than Philip Guston, a leading Abstract Expressionist painter who died in 1980. He became known in the 1950s and ’60s for juicy, heavily textured, nonobjective paintings; during the 1970s he shifted to cartoonish depictions of the Ku Klux Klan but retained his painterly touch. Meanwhile, Kadish, who never rose to fame, gave up art in the mid-1940s and worked as a dairy farmer for about 15 years. He re-created himself as a sculptor in the late 1950s but gained little notice.

Goldstein is remembered–as Guston–for paintings so different from the City of Hope mural that few would guess he is one of its creators. Born in 1913 to Russian immigrants in an impoverished Jewish section of Montreal, he was the youngest of seven children. In 1919 the family moved to Los Angeles, where Phillip’s father made a living by collecting refuse on a horse-drawn wagon. The boy had little contact with fine art, but he had an aptitude for drawing and loved comics. In an early validation of his talent, at 15, he won a cartooning contest for teenagers run by The Times.

When his winning cartoon was published in the newspaper, Goldstein was a budding artist at Manual Arts High School. One of his classmates was Jackson Pollock, who became the most celebrated figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Rebellious and openly critical of everything from traditional teaching methods to social injustice, the two teenagers were expelled in 1928 for distributing satirical pamphlets about the school’s English department and lodging protests against the athletic program and ROTC.

Pollock finished high school after his ouster, then moved to New York in 1929, studied painting at the Art Students League and urged his buddy to join him. Goldstein refused to go back to Manual Arts but stayed in L.A. He worked at odd jobs and in 1930 won a year’s scholarship to Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design). Finding the teaching insufferably pedantic, he left after a few months but forged connections in the art community, partly through his friendship with Kadish, whom he met at Otis. Lorser Feitelson, an influential painter and teacher, became Goldstein’s mentor and took him to see the collection of Walter and Frances Arensberg, who had moved their vast avant-garde holding of modern art from New York to Hollywood.

Goldstein also fell under the spell of Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros, who had come to Los Angeles to paint a wall on Olvera Street, and Jose Clemente Orozco, who had been commissioned to paint a fresco of Prometheus at Pomona College in Claremont. An outspoken leftist who used his artistic skills to protest racism and other social evils, Goldstein wanted to do public projects on a heroic scale. Around 1931 he and Kadish traveled to Morelia, Mexico, where they painted “The Struggle Against War and Fascism,” a 40-by-25 1/2-foot mural in Maximilian’s summer palace, under the sponsorship of Siqueiros.

After Goldstein and Kadish returned to Los Angeles, Time magazine ran a photograph of the mural with an article characterizing the artists as “parlor pinks.” They feared the label would damage their eligibility for public projects, but–through a cousin of Kadish–they won the commission at the City of Hope, then a tuberculosis sanatorium run by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. The artists spent about a year designing and painting the fresco in a building designed as a medical library.

In 1936, when the project was complete, Goldstein followed Pollock to New York, in search of opportunities to paint murals. He immediately signed up with the mural division of the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration, established under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Goldstein had embarked on a new phase of his life, complete with a new name. He changed the spelling of his first name to Philip and switched from Goldstein to Guston, apparently to win the favor of his future in-laws, the parents of Musa McKim, an art student he had met at Otis and married in 1937. Embarrassed about his action, Guston later concealed his name change and even repainted signatures on some of his early work.

As the years passed, Guston’s focus evolved from figuration to abstraction and from public murals to studio work. Meanwhile, the mural in Duarte was largely forgotten. During the 1960s the medical library was converted to a graphic arts facility and divided into cubicles. The mural wasn’t painted over, but furniture and office equipment rubbed against it, water seepage eroded lower sections, parts of the fresco pulled away from the wall and the surface of the painting developed pockmarks and blisters.

The artwork might have been left to deteriorate if a fortuitous meeting hadn’t occurred at a dinner party about two years ago. Ernest Lieblich, president of Foodcraft Services in Los Angeles and a longtime patron of the arts and the City of Hope, had noticed that the medical center had beautiful grounds but no art. As he saw it, the institution was missing an opportunity to create a nourishing environment, so he expressed his concern to another guest at the party, Robert J. Reid, associate vice president of donor relations at the City of Hope.

Sensing an opportunity, Reid asked Lieblich if he had seen the mural. The answer was no, so they made a date a couple of days later.

Touch-up: Aneta Zebala, foreground, and Marisa Kuizenga help restore the small parts of the mural. Photo: Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times

“The building was a terrible mess,” Lieblich said. He had entered through the door on the mural wall, so he couldn’t imagine what Reid had in mind. “Then I turned around and saw this huge mural. It was amazing, but it was awfully neglected,” he said.

Reid knew little of the mural’s history, much less the artists who had signed it. But Lieblich was fascinated, so he asked a friend to help him do some research and discovered that Goldstein is Guston. The revelation heightened Lieblich’s interest, and he agreed to finance the restoration of the mural and the building. The cost of the project has not been disclosed, but Lieblich said he has made “a sizable donation.”

An energetic entrepreneur who pulls out all the stops when it comes to supporting his artistic passions, Lieblich delights in seeing the mural restored to its former glory, but he describes the process as “a long, long battle” fraught with frustrating delays and bureaucratic processes.

“When you are a businessman, you decide to do something and you just do it,” he said wearily.

Delays were caused by the difficulty of doing a historical restoration in a building that had to be brought up to current codes of lighting, air conditioning and access for the handicapped, but the project was well worth doing, said Charles M. Burch, president of the City of Hope. “The mural and visitors center represent an important part of the history of the City of Hope. Because of the beauty and significance of the mural, we wanted to restore it to its original condition so that people could enjoy it.”

What visitors will see is not only Guston’s and Kadish’s youthful artwork but the result of extensive cleaning and conservation by Eduardo P. Sanchez, assistant conservator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. He undertook the City of Hope job independently in collaboration with Aneta Zebala, a private paintings conservator, and her assistant Marisa Kuizenga.

“It was a wonderful project,” said Sanchez, who also has worked on the Orozco fresco at Pomona College in Claremont and a mural by Alfredo Ramos Martinez at neighboring Scripps College.

At the City of Hope, he oversaw a team effort that took about 2 1/2 months. John Twilley, senior conservation chemist at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, analyzed the pigments and binder, while Chris Stavroudis, a private paintings conservator, examined the mortar and helped to devise a plan for treatment.

“What was found was surface disturbance due to salt activities,” Zebala said. Salts in the plaster had crystallized and migrated to the surface over the years, causing a plethora of distracting blemishes that were particularly prevalent on flesh tones.

“In addition, there was a heavy accumulation of grime,” she said. “It was a greasy type, and it was evident throughout the mural but principally at the top [because of air currents and exposure from adjacent windows]. There was also cracking at the top edge of the mural, probably caused by seismic activity.”

Treatment entailed cleaning the surface, consolidating flaking paint, filling cracks with adhesive, and then painstakingly retouching the paint–filling in thousands of specks. In keeping with current conservation practices, all changes to the painting are reversible, Zebala said.

The City of Hope’s new visitors center, with the restored mural as its centerpiece, is the first step in enhancing the medical facility as “a place of healing,” Reid said. Located near the entrance to the grounds, the building will function as an orientation point, a gallery for exhibitions and a reception space.

The restoration is “a terrific thing,” said Robert Storr, author of a book on Guston and curator of the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “It’s part of a general reclamation of murals from the 1930s that are a very important part of American art history.” The move to save these paintings, including Siqueiros’ mural on Olvera Street, is happening at “the last moment” before the murals crumble and the buildings are destroyed, he said.

WPA-era murals by young artists who later became known for another style of painting have been treated as necessary but insignificant stepping stones in their evolution, Storr said. But Guston’s late, figurative work, which returned to the political thrust of his early painting, makes it clear that his “vocabulary was defined in the process of making murals,” he said. “His murals are not only an interesting part of American art history, they are important in their own right for their artistic qualities.”

The medical center’s Reid said the restoration signifies “the beginning of the City of Hope’s relationship with the arts.” Plans are in the works to solicit, acquire and display other works of art, including outdoor sculpture. But for now, the big attraction is the mural. “I think it’s going to be an eye-opener,” he said.

City of Hope is located at 1500 E. Duarte Road, Duarte, California