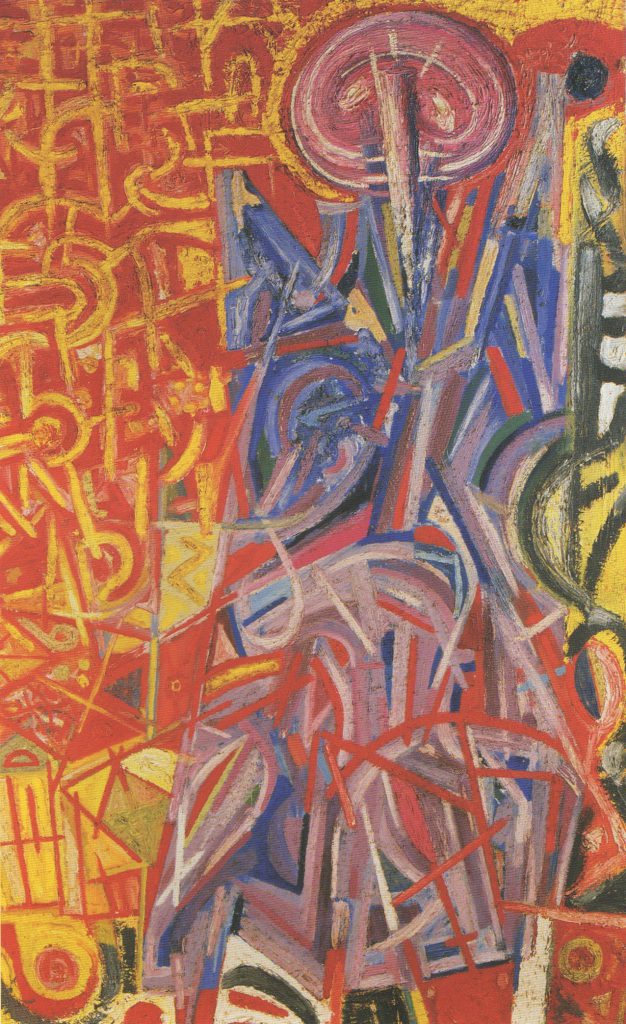

untitled, oil on canvas, 44×27, 1947

A brutish, bulging figure, mold-ed and pinched from clods of clay, lies on the floor near a window. Its scrawny arms wave helplessly in the air, its upturned face — part insect, part human — contorts into a mute howl. Meet Gregor, a sculpture created in 1965 by Reuben Kadish, and the centerpiece of a tiny but powerful retrospective at the Pollock-Krasner House.

Gregor, who is named after the main character (changed overnight into a cock-roach) in Franz Kafka’s story “The Metamorphosis,” could well be a stand-in for the artist. Kadish began his career as a muralist, cocooned himself for several years on a dairy farm in New Jersey, and reemerged as a sculptor of disturbing, savage totems. Unlike Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, Kadish flourished in his new guise, even if his transformation was fraught with pain.

Born in Chicago in 1913, Radish grew up in California. Early on, he formed an association with the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose style and political commitment he emulated. But a stint in the Army Artists Unit during World War II exposed him to the raw suffering of war in Asia and imprinted an unrelieved morbidity on his psyche. His postwar work took on a darker tone: Corpses, skeletons, serpents and monsters took up permanent residence in his paintings and drawings.

Even with death lurking everywhere, Kadish remained something of a sensualist, partial to a particularly lovely shade of pink. Traces of that rich, rosy color appear near a frightful figure’s shoulder in a 1945 work, and in the bright patterns and chunky surface of a more abstract 1947 painting.

It was a year later when Kadish removed himself from the art world entirely. In 1958, when he rejoined the scene, it was as a master of terra-cotta. Kadish’s sculptures are pointedly crude. “Head” of 1962 looks like an ancient idol with gaping eyes, a slit for a nose and a series of pimply protrusions studded around the cheeks and neck.

“Gregor,” terra cotta, 14x33x16, 1965

“Cocoon III” (1977) returns to the theme of metamorphosis. A knobby insect, eyes bulging, emerges from its chrysalis. This is no graceful butterfly, but a tough bug whose scabbled carapace hints at a lifetime’s worth of conflict.

As a sculptor Radish was able to indulge his penchant for sensuality. He evidently savored the feeling of clay in his hands and relished squeezing, shaping and probing it as he created primal forms out of the earth itself.

Toward the end of his life Kadish returned to paper, completing a group of monotypes that synthesized all he had done before. Hybrid creatures writhe, serpents twist amid shoes and bones, and death declares its ascendancy.

Despite all the teeth-gnashing in his work, the Pollock-Krasner House show is far from depressing. It demonstrates how constructive and fertile rage and terror can be, and how contemplating mortality with sufficient technique can produce art.