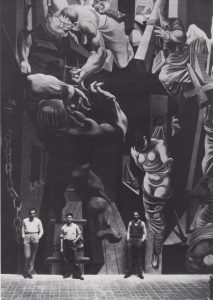

1935, Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner in front of the mural, “The Struggle Against Terrorism”, 1934-35. Center section of fresco at the Museo Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico. 40 ft. high

There are numerous instances of 20th century American pointers, such as Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman, who took up sculpture at some point in their careers. Conversely, sculptors such as Alexander Calder and David Smith experimented with painting. But there aren’t many painters who radically trans-formed themselves into sculptors and resolutely soldiered on in that demanding, three-dimensional field. Reuben Kadish (1913-1992) is a stellar example.

According to family lore, Kadish was a precocious draughtsman. By the time he was in his early 20’s he and his mural painting partner, Philip Guston (then known as Philip Goldstein), were hailed in Time magazine by their mentor, the famed Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, as the most promising painters in either the U.S. or Mexico.”

Kadish had met the charismatic Siqueiros in 1932 in Los Angeles and volunteered as his assistant on mural proj-cts—or, as Kadish described his role in an oral history interview with the Archives of American Art, a “go boy for this, go boy for that.” In 1934 he, Guston and Sande Pollock (Jackson Pollock’s older brother) painted their own mural at the Workers’ Community Center, signing it, in emulation of the revolutionary Mexican mural collective, as “The Syndicate of Painters.” By this time Siqueiros was back in Mexico, and Kadish sent him photo-graphs of the mural. Siqueiros was impressed and excitedly invited the young artists down to Mexico, telling them he had work for them. Sande Pollock didn’t make the trip, but Kadish and Guston were commissioned to paint a mural in Morelia.

Lamentation, 1935. Oil on panel, 16 x 25 inches. Private collection

The Morelia mural of 1934-35, provocatively titled Struggle Against War and Fascism (or La Inquisicion, as it was known in Mexico), was quickly followed by Physical Growth of Man, another mural collaboration with Guston, at the City of Hope sanatorium in Duarte, out-side Los Angeles, in 1935-36. That ended Guston and Kadish’s remarkable collaborations, but Kadish went on to execute a solo mural, A Dissertation on Alchemy, at the San Francisco State College Science Hall, in 1936-37. Like the Duarte mural, it was commissioned under the aegis of the government-sponsored Federal Art Project, part of the Works Progress Administration.

During World War II Kadish worked as a steelworker in shipbuilding before being recruited in 1943 to document the war effort as an official Army Artist. It was an elite unit comprising some of the best-known American artists of the time. Kadish was just 30 years old. He requested posting to the European Theatre but was sent instead to India and Burma, where he encountered little battlefield action but found an abundance of abject civilian suffering, hunger, dislocation and misery. The Post-Surrealist influences he had hungrily imbibed in Southern California, in part under the tutelage of painter Lorser Feitelson—whose influence can be readily seen in Kadish’s paintings of the 1930’s such as Lamentation, as well as some aspects of the Morelia mural — were jettisoned and replaced by a razor-sharp documentary style, seething with emotional energy and social concern.

The brutal images he drew of emaciated figures and skeletal corpses occupy-ing devastated and scarred streets—two of which are in the current exhibition—kindled the expressionist flame that Kadish kept burning throughout his long career. His experiences in the storied Army Artists Unit and intense travels to the ravaged streets of Calcutta and other downtrodden places had a profound impact on his later work, planting the seeds for his transformation into a sculptor. For, although never confirmed in so many words during his lifetime, it seems that Kadish also took home the mythological richness of India—powerful images of the exotic architecture and carved stone figurative sculpture of ancient cultures that would so transform his artistic vision.

Earth Mother IV, 1968-69, Terra cotta, 60x24x8

That process slowly developed after the war, when Kadish spent a few years in New York City, where he painted the small group of untitled paintings from the mid-1940’s that make up part of this exhibition. They represent some of the last examples of his two-dimensional work on canvas. The churning surfaces, some rough with the mix of sand and oil paint, are also densely crosshatched with marks resembling hieroglyphic symbols in blazing hues.

In 1948 Kadish settled with his young family at a rundown dairy farm in then-rural Vernon, New Jersey, sixty winding miles from Manhattan. It was a time of fierce and painful struggle: Kadish, the new farmer and family man trying to make a living; and Kadish the artist fighting to find his way in paint, for from the bubbling tumult and excitement of Manhattan and the burgeoning New York School. “I could have been living in Kansas,” he ruefully recalled in a 1992 interview for the Archives of American Art. “It was really one of the major mis-takes of my life.”

Stories of a devastating studio fire at the farm that destroyed many of the paintings created after the War couldn’t be confirmed by Kadish’s oldest son, Dan, who still lives there; he believes it was more of an emotional conflagration, in which the artist deliberately destroyed his own work. In a recent telephone interview, Dan Kadish also recalled that, as a teenager in the early 1950’s, he spent long hours with his younger brother Ken in the backwoods of the farm helping their father dig trenches in the rich earth and fill them up with field stone and con-crete. Apparently the structures they created had no utilitarian purpose. Dan Kadish believes that these earthworks were his father’s earliest sculptures, now buried and unmarked as some still undiscovered archeological wonder.

Double-Jack, 1958, Bronze, 30 x 16 x 16 inches. Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Though isolated for a critical period from his New York peers, Kadish began to develop his own sculptural vocabulary, first in the medium of clay and carving directly into the pliable material with the sharpened point of a rib from a pig he had slaughtered for the family table. He eventually turned to bronze casting and his growing progeny of expressionist figures, such as Double-Jack (1958) Queen of Darkness and Wandering Oedipus (both from 1959), represent some of his first mature works in sculpture. His series of larger-scale earth mothers and other potent fertility goddesses, such as Demeter and Indira, would not appear until the latter part of the 1960’s, further confirming the immense impact of his India experience.

That decades-long distillation of influences melded with Kadish’s experience as a farmer intimately involved with seasonal cycles of life and death, growth and decay.

It is interesting to consider his 1965 terra cotta, Gregor, named after the central character in Franz Kafka’s story, “The Metamorphosis,” as a metaphor of Kadish’s own transformation from painter to sculptor. Cradled in a crudely fashioned wooden bed, its stubby legs anchored by flimsy wires, Gregor con-templates his bizarre fate. The stocky, terra cotta sections of the reclining fig-ure/bug, with its upturned legs and pincer-like fingers, creates a ferocious presence. The scored lines that tattoo Gregor’s armored body, as if a kind of tribal marking, further invest this creature with a quirky authenticity. The figure, simultaneously playful and disturbing, rattles and challenges the viewer with the title’s literary reference. (The first line in Kafka’s tale reads: “Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams and found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”)

Though Kadish underwent a decidedly different kind of transformation, his long journey also achieved extraordinary and surprising results.

Gregor, 1965. Terra cotta, 14x33x16 inches