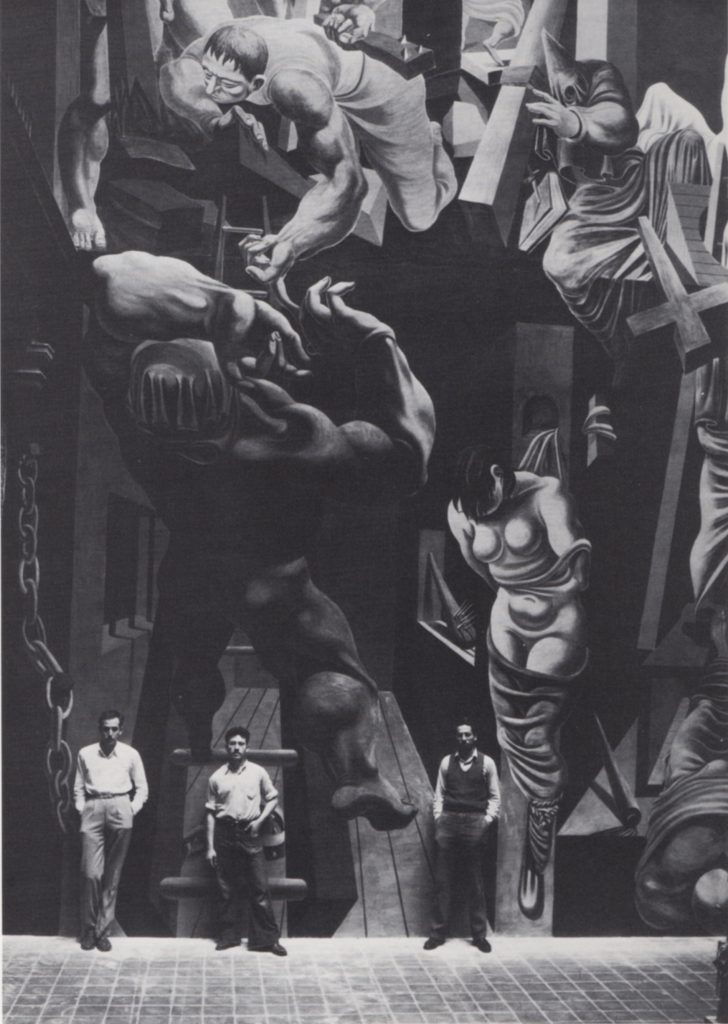

1935, Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner in front of the mural, “The Struggle Against Terrorism”, 1934-35. Center section of fresco at the Museo Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico. 40 ft. high

Forward

In the works of Reuben Kadish the remove of our intellect couples with a sensual immediacy — a studied depth with an ease of response — to create a layering of idea and emotion. Parables of our struggles, our weaknesses and our resilience, these etchings of our concerns and involvements deeply penetrate the core of this work and thus of our consciousness. Both the drawing and the painting of the 1930s and 1940s and the sculpture of the last thirty-five years make this dialogue evident. The vantage point, the Socratic conscience, is apparent from the beginning of Kadish’s career. He has never relinquished his commitment to the social and ethical avant-garde. In his work, the purely sensory is wedded with the weight of introspection, one which finds its integrity through a material response. The use of materials — terra cotta and bronze — yields a palpable and forceful statement about our visceral relationship to the world. They are suggestions of human failure and frailty, traces of our beginnings and endings.

Born in 1913 with beginnings rooted in the artistic and the social climate of the 1930s, Kadish’s exposure to anarchist beliefs, strengthened by his commitment to social equality, shaped his early works. Social and political discourse was integral to his development as a thinker. Since his youth in California, Kadish has married humanitarian beliefs with his involve-ment in art. His forthright portraiture of the 1930s, indicative of the solid and foreboding presence that imbues his works of this decade, underline a respect for the plain and unadorned.

A passionate concern for the morass of humanity has informed Kadish’s works over the past six decades. The imagery of his figurative works reflects his regard for global issues. However, an underlying awareness of these issues penetrates the core of his abstract works of the past forty-five years. Throughout, the ethereal and the metaphysical occupy the same realm as the visceral and the earthly. His works mirror the political struggles of the time. They blend the social realities of Western culture with elements of Eastern symbolism. While these works bear the imprint of concerns important to a specific era, they can still clearly be read in a personal context.

A sculptural intelligence exists in the early paintings and drawings. An imposing muscularity permeates the imagery and thus informs us of its gravity. A painterly involvement is integral to the more recent sculpture, in part made evident by the frontal orientation and the richness of surface. In these works, deeply incised line structures form and volume. Folds and crevasses emerge to layer nuances of experience. Encrusted and incised with Kadish’s beliefs and experiences, this involvement in surface aligns these works with the tradition of Abstract Expressionism. Allusions merge. The mythological joins the sensual. The temporal is given a foundation. Metaphors of our history, these statements speak to the world. Overlays of mean-ing, imbued with an intelligent solidity and a material density, the works embody a life force.

Common to all works is a strength of conviction. They press on our consciousness an awareness of our history and give physical presence to the moral questions of our time. A visceral strength and an ethical understanding, seemingly injected into the vein of Kadish’s work, strengthen and give purpose to the most straightforward of his figure studies. The passion that underlies the more removed imagery of the 1930s pulsates by the works of the 1970s and 1980s. His need to respond to specific issues has broadened in scope, speaking on a personal and global level. A firmness of commitment to social justice visible in the figurative allusions of the paintings and drawings is also evident in the density and the hardness of the materials Kadish uses in later sculptural works.

Reuben Kadish

Allusions to states of aggression provoked the works of Reuben Kadish throughout his career. The recurrence of warfare and conflict is seen by Kadish as a defining quality of our existence, and is of utmost concern in the interpretation of these works. The state of the world is ques-tioned. From the beginning of his career he has made evident his disinterest, or perhaps in-ability, to portray tranquility. This response to the world has taken different forms — from his mural work in Mexico and San Francisco during the 1930s; his work executed as a member of the army artist unit in 1943 and 1944; the frenetic abstractions of the mid-1940s and 1950s and again in the skeletal abstractions of his Memorial series of the 1960s; to the anatomical displacement of the works of the Earth Mother series and the anxiety-ridden figure studies of the 1970s. By the 1980s this concern exerts a formidable presence in the Holocaust series and in the intimate yet powerful figures of his Aggressive Personage series.

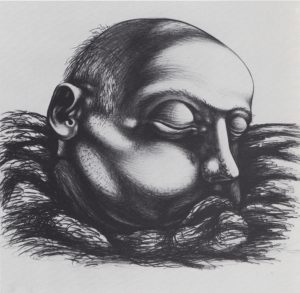

(cat. #6), untitled, pencil on paper, 15×16, 1935

The first mature works of the 1930s, figurative paintings, contain an anguished vision of struggle and alienation. A directed strength is present; yet the works are imbued with a contemplative, introspective quality that gives the subject an inactive presence. Form is sculpted with precision, yet the sculptural definition of form imparts a solidity and reveals a coarseness of our physcial nature. Kadish sees beauty in the unrefined essence of life. A belief in social realism is present throughout his oeuvre and is implicit in his depiction of ungainly features. This concern first becomes evident in Portrait of Mother’s Friend, The Artist’s Father, and the Portrait of Enrico Biagio, Alaska Fisherman (cat. #10). Jowls and eyes are sensuously sculpted into abstract forms; facial hair enlivens quiet surfaces; and physical im-perfections become the ideal. In the mural at the University of Michoacan in Mexico, de-signed and executed in collaboration with Philip Guston and J. M. Langsner in 1935, a sculptural foreshortening depicts Promethean figures unshackled in their struggle for freedom amidst a whirl of hooded Klansmen and other political and religious symbols. This work affirms the reality of the visceral struggles of our existence. This integrity of thought remains visible over the next fifty years.

Kadish makes our isolation further evident in the self-containment projected by these por-traits. He does not establish a dynamic relationship between the viewer and the sitter. The portrayed become the seers and the judges of our history. Kadish assumes this removed position in the untitled drawing (cat. #6), c. 1935, where innumerable horrors are implied. A severed head implanted on the horizon, inward and enclosed with its buried mouth and closed eyes, reveals our foreboding thoughts and actions. A tear is shed by this cadaver, a symbol of our conscience and our humanity. This imagery, timeless in its presence, speaks of the past, present and future. An involvement with our intellectual position in the world is underscored by the use of the head as a metaphor for our consciousness and for our conscience. Through the use of this metaphor, the artist implicates the intellect as a possible cause of this devastation. This confrontation with aesthetic and social values would occupy him for decades.

(cat. #204), Dream, terra cotta, 24x19x10, 1986

Nakedly positioning a severed head on a plane, a worldly horizon, will again become part of Kadish’s vocabulary in the Holocaust series of the 1980s. Again, imagery of the head as a vessel of our knowledge and history underlies the integrity of his statement. Once again, our intellect is implicated — the world’s destruction results from acts conscious and knowing. Depersonalized yet human in their presence, abruptly severed at their necks, these heads impose on us. Kadish began the series in homage to the millions of victims of war. In these works, motivated by our numerous holocausts and anonymous victims, the imagery is archaeological with an unearthed presence. Terra cotta and bronze, the imagery has a physical density integral to the material, yet it also mirrors the intellectual and emotional layering of messy worldly issues and gives a voice to political and social strife. The response to our many injustices is immediately felt in the palpability of the terra cotta. The clay is pressed and chiseled with force; marks are laid down and negated by other marks, to create a fossilization of history. He has given this sculpture a painterly surface, with an active field of line and nuance. The skin is treated like a two-dimensional plane. The surface is baked and dried, delineated and scored with a cubist approach to structure. The narrative is abstract. In Dream (cat. #204), a work from 1985, a hand rests atop the not quite open mouth, again creating a self-containment, a continuous cycle — moving across and around the face rather than penetrating the voids and orifices of the skull. The eyes read as bulbous slits and function as armored projectiles. A recent head from 1988, references several cultures, the scarification of the African, the headdress of the Native American, to merge the historical with the present and the indigenous with the modernist. Appropriations from various cultures and traditions have nourished Kadish from his beginnings. However, unlike the appropriation of today, Kadish has assimilated his sources to create objects imbued with an integrity germane to his personal search. These works, vitrified memorials to our past and provocative monuments of our future, portray all humanity.

In 1943, Reuben Kadish was invited to serve the country as a member of the army artist unit in World War II. His exposure to the realities of warfare in the arenas of Burma and India subsequently influenced his involvement with the world. An unavoidable response to the over-powering devastation and death of his wartime experience supplanted the obscure and ethereal intellect seen in the surreal imagery of the 1930s. Furthermore, his involvements with social realism, rooted in the personal, now address the global and the far-reaching. Though stemming from a broad, historical awareness and directly confirmed by his wartime experience, his involvement with this imagery of death was causal. His work, imbued by a depth of expression, makes our mortality apparent. A reflection of misery, these works record the trials and the struggles that have since permeated our existence. They reveal the futility of our existence and our inability to affect the forces of our global environment. In this instance, the extinction of our individual worth, through the destructiveness of the Japanese bombing, was decisively important. The imagery portrays stiffened corpses on the streets of Calcutta —exploded men still intellectually aware of their near state of death and the inhumanity of the victims’ homelessness and starvation. Kadish’s exposure to the many blackened and encrusted bodies and buildings and trees uprooted and torn asunder left an indelible mark on his psyche. Yet, a spiritual undertone is given to these images of death by starvation, to these pyres of charred bones and landscapes of cataclysm. Victims of war are drawn in embryonic positions. A sense of the cyclical nature of life is evident through his use of compositional devices. His awareness of Eastern philosophies becomes obvious in these brutal works to which he gives a layer of consciousness not neccessary for the depiction of warfare. For the next forty-five years, Kadish will continue to address the imminence of warfare.

Kadish’s involvement with Eastern mysticism began while in San Francisco in his youth with exposure to these teachings. After having left high school as a result of his political in-volvements, his learning was independently structured. An avid reader, Kadish embraced the indigenous and the non-western. In 1927 at fourteen years of age, he began an appren-ticeship of nearly six years to the post-surrealist painter, Lorser Feitelson, whose belief in associative thinking and respect for the Renaissance distinguished his teachings. His works were removed and intellectual in their outlook, merging the natural with the artificial. In Kadish’s 7 more surreal works of the 1930s, Lamentation, 1935, his mural, A Dissertation on Alchemy, 1936, executed during his tenure with the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project in San Francisco at the State College, and Conversation with a Quarry Master, of 1937, one can identify the teachings of Feitelson. His pensive introspection is evident. These values would affect his future expressionism and in part provide the basis for his involvements with diverse cultural and mythological sources.

In some imagery, the statement underlying the work imparts a specific message while all works make apparent the richness of his visual language. The receptor of his message has changed from the collective audience of the mural executed with Philip Guston in 1934-1935 at the University of Michoacan in Mexico and subsequently of the mural, A Dissertation on Alchemy, 1936-1937, for the San Francisco State College in California to the individual viewer of the intimate objects of his Aggressive Personage series. In the mural works of his youth, Kadish expressed broad ideas to masses of people. Now, similar ideas underlie objects that require an intimacy with the viewer. A shift from the impersonal mass to the individual precedes the shift from painting to sculpture.

(cat. #75) Duo II, Encounter, bronze, 34 x 12 x 8, 1959

Leaving New York City in 1946, arduously dairy farming in Vernon, New Jersey, allowed Kadish time to reflect and assimilate his World War II experiences. During this time of reflection away from the center of the art world, he would decide to continue his work as a sculptor rather than as a painter. The bronze and terra cotta works of the 1950s enclose and balance discrete form. Analytical in their movement, planes and tubes form aggregates invested with a visceral force, organ-like in their presence and cellular in their structure. Suggestions of weaponry are evident in the works, Seer I and Double Jack, both of 1958. Foreshadowing the Aggressive Personage works of the 1980s, these sexually referential symbols are also seen as equivalents of the offensive. In Duo II, Encounter (cat. #75), an economic building of cones and arched planes, constructs an embrace between two figures. In this quiet work, the painterly activity contained in the surface predicts his future response, one that would develop into encrustations of time and memory. Blackened patinas give these works a density of tone. Abstractions with a biological impact, their understanding derives from life experiences. A personal response to the cyclical nature of our existence has been apparent from the early works of the 1930s and the drawings of the 1940s made on his return from Asia.

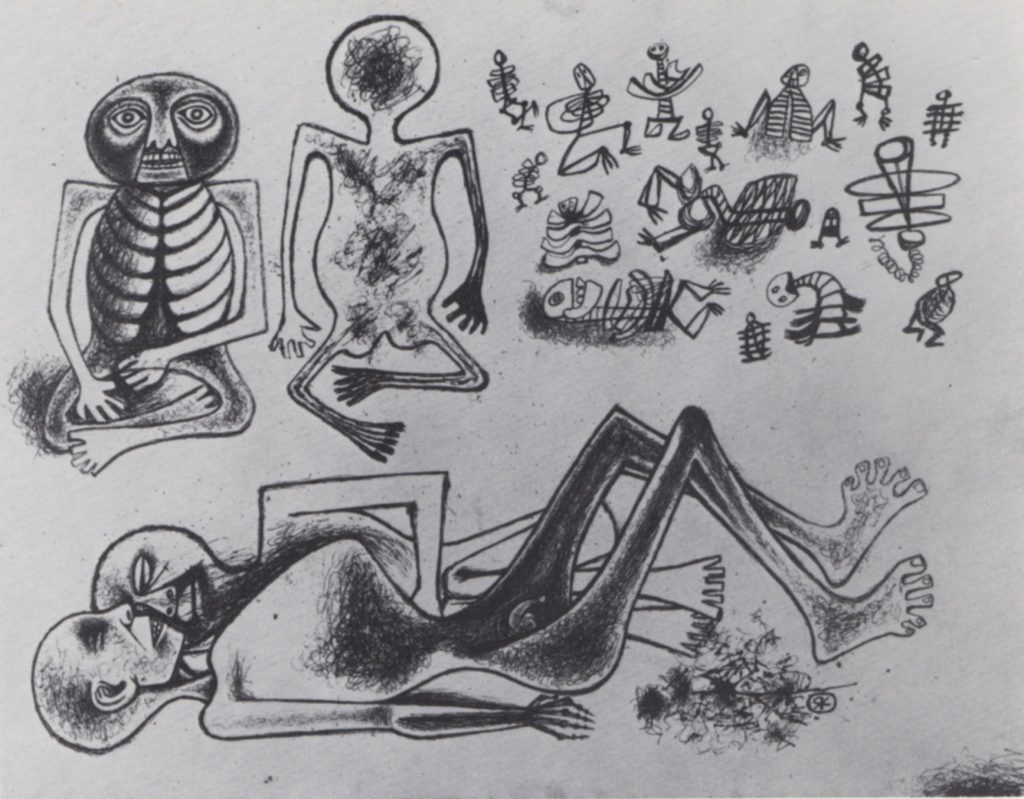

Document Famine, india ink on paper, 19 x 25, 1944

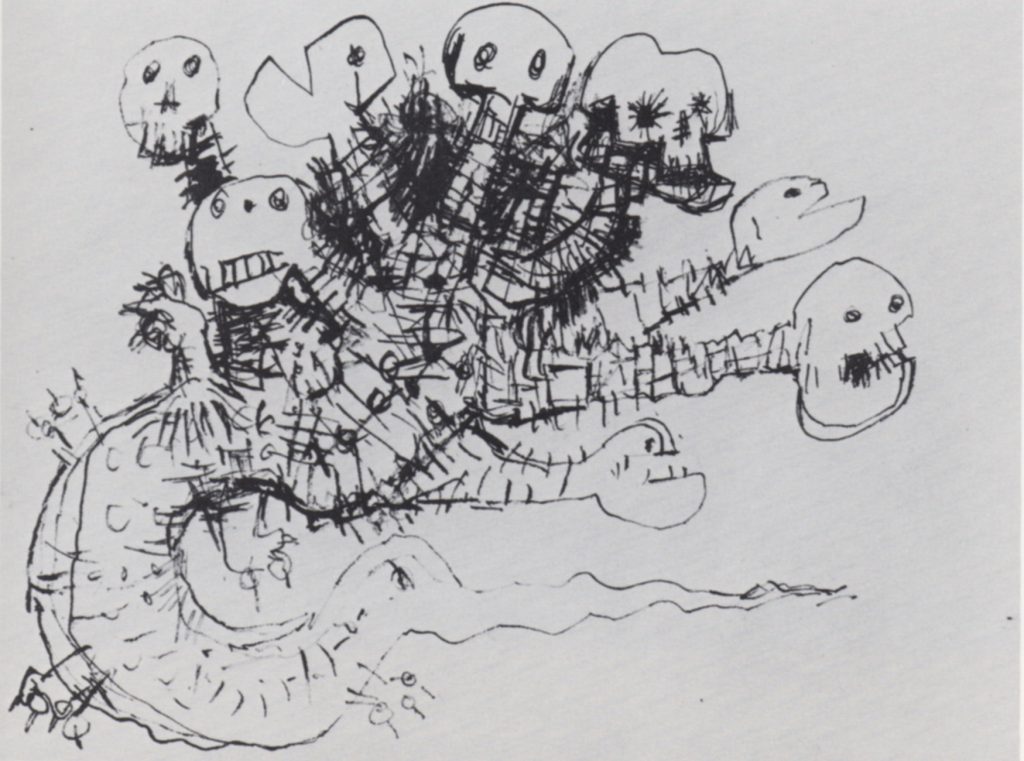

In Document-Famine-India, Cycle of Sorrow, and the untitled drawing, all 1944, a spiritual tone imbues the imagery. Within the narratives, a dog pulling the entrails of a corpse, graffiti-like line drawings of emaciated men, is an underlying cyclical awareness. This is also evident in the conjoining of elements. Tubular missiles welded to ovoidal structures form uninterrupted passages. To Kadish, the extreme heat of the casting and pouring of bronze and the firing of terra cotta bespeak the outcome. The activity of the object mirrors this generative force. A disinterest in producing objects of perfection coupled with a regard for the mystical equivalents seen in firing informs these works. The artist remains a tool of an overpowering force. The works embody an ethereal presence with material understand-ing. In the Memorial series of the early 1960s, limb-like forms reach upward in totemic structures. Weathered fragments of bones form girdles, skeletal support systems stripped of their substance. Again, these are memorials to innumerable victims. In the works from the Vietnam series of 1968, succinct yet crude line drawings indicate violence and destruc-tion. These drawings portray exploded skeletal remains with snake-like spirits entwining and invading the carnage. In the untitled work, a spinal column emerges from a bed of snakes. The snake’s image becomes the rib cage and the horizon line, evolving into both 9 an individual and worldly life force. In another untitled work of this series, a myriad of snakes becomes a horizon, again drawing a comparison to the untitled drawing of the head from c. 1935. Throughout, Kadish will use this metaphor to speak to the world.

untitled V, Vietnam Series, ink on paper, 9 x 12, 1968

The tension of the underlying statements assuming more importance than the visual work may underscore Kadish’s career. While evident in the chosen titles for various series of works, such as the Holocaust series of the 1980s and the Memorial and the Vietnam series of the 1960s, it is not present in the works occupied with mythologically related imagery or figure studies. The vision of these works does not share the ghostly impact of our many holocausts. However, a similar intensity exists in the female nude and the holocaust victim, the imagery of Aphrodite, Medusa or a figure set in the wreckage of Vietnam. Kadish has chosen the sensuality of the figure and its bared skeleton as vehicles to represent our essence. The malleability of our flesh contrasts with the hardness of our skeleton. These works pare away the nonessential and alter our perception of our core. Thighs emerge from breast-like forms or evolve into shoulders and heads in the bas-reliefs of the Earth Mother series. Kadish presents the woman, a recurring metaphor, as a symbol of fertility and power, a force of torment and elation. A bovine presence permeates these depictions of the female. The untitled terra cotta works from the Earth Mother series, c. 1958-1959, are imbued with a raw expression, immediate in its presence. Suffused with an understanding of birth and death yet given the posture of a deity, this work merges religious awe and the rudimentary understanding of the farmer. These may be seen as monuments of fertility. Slashes and deep incisions abut swollen and weighted forms. Breasts multiply and mutate as shoulders and heads, stomachs and thighs. However, for the most part, the head is left untreated and negated by this overripened fertility. In Split, a work from 1970, the spinal column parts beneath the head; an empty field fills the void, leaving no support. In the more traditional figure studies of seated women, the activity of Kadish’s material response negates the sculptural solidity of the model. Figures formed by a multitude of pinched plains transport the work to an immaterial realm. Energy is portrayed rather than material, responsiveness rather than actual presence. While traditional in their portrayal of a studio model, the recording of emotion draws the terra cottas to their Abstract Expressionist beginnings. In Jocasta III, a terra cotta work from 1976, a seated woman emerges from his probing and unsettled touch. Nodules adorn the torso; snake-like forms function as the head. Throughout much of Kadish’s imagery, the foreign over-powers the native.

In the Aggressive Personage series, Kadish endows ancient mythological entities with a contemporary presence. Constructs of snake-like forms function as rib cages and pelvic girdles. Coiled snakes enwrap and envelop our actual anatomy: the snake supplants the skull and our reproductive organs to become a metaphor for an invasive force. The human joins the reptilian. These works are intimate in size, directly resulting from a hand-cradled response. Functioning as power objects, their scale belies the impact of their statement. Extroverted in stance, the works speak of the carnality of the world. However, a serenity of vision prevails, suffused with a mythic intimacy. An acceptance of our basic struggles allows a forwardness of vision. Myth Xl, c. 1984, is both female and warrior. Comically human yet fiercely aggressive, these works speak of our contemporary fate.