Fig. 1, Reuben Kadish (American, 1913-1992) Head (Portrait of the Artist), 1985 Bronze, 22.5 x 17.5 x 18.75 inches, MSU purchase and partial gift of the Estate of Reuben Kadish, 2000.5

Born in Chicago on January 29, 1913, to immigrant parents from Kovno in Czarist Russia (now Lithuania), Reuben Kadish was the oldest of three sons. The family moved to Los Angeles in 1920, and that is the primary place where the soon-to-be artist developed strong roots and lifetime friendships. His father, Samuel Kadish, was a painting contractor by trade but also harbored strong political interests, having been a member of the Marxist-oriented Bund in Kovno while a young man in pre-revolutionary Russia. The Yiddish-speaking household was rich in books and magazines though the artist’s father had stopped his formal schooling at age ten, according to a Roots-like account written late in life by his middle son, Frank Kadish. But Kadish the patriarch was quite artistic in his own right as a trained decorative painter, expert in various decorative painting techniques such as faux bois and marbling. Something must have rubbed off on his first son Reuben, who, early on, drew everything in sight.

Politics also played a vital part of that family brew as Reuben became a teenaged political radical in the early 1930s, leading a protest against U.S. Marine presence in Nicaragua, decades before the Sandinistas of the Reagan era. As a result, he was unceremoniously expelled from high school. Soon after, Kadish briefly became a serious student at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and quickly befriended two young men who not only would become lifelong friends, but would later wield an enormous influence on the postwar art world, Philip Goldstein (who later became Philip Guston) and Jackson Pollock.

Goldstein and Pollock had been classmates at the Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles until both were similarly booted out for distributing satirical pamphlets. Though Pollock never studied at Otis (he moved to New York to study at the Art Students League with Thomas Hart Benton), he often visited Los Angeles, remaining close with Guston and striking up an instant rapport with the intense, bespectacled Kadish.

In a 1992 oral history interview with Stephen Polcari for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art,1 recorded barely five months before the artist’s death from complications of leukemia, Kadish spoke of the tremendous”energy and vigor” of Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Benton. “The main thing I got out of these people is that they were interested in big ideas.” That early and critical impression stuck with Kadish throughout his life and ultimately translated into his greatest work, his powerful series of terracotta and bronze Memorial heads created in the mid-1980s, and of which Portrait of the Artist (fig. 1) is a quintessential example.

Looking backwards to that super-charged apprenticeship in Los Angeles, Goldstein and Kadish soon grew tired of Otis and set up a studio nearby where they continued their self-taught studies in Renaissance painting. The work of the Mexican muralists had a growing influence on the young pair. In fact, the duo would soon make a big impression of their own on the famed Mexican muralist and left-wing firebrand, David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974). Kadish had already volunteered his services to the charismatic figure and chauffeured Siqueiros around Los Angeles, assisting him on local outdoor mural projects in fresco on cement such as La America Tropical at the Plaza Art Center on Olvera Street in 1932, depicting a crucified peon with a group of Mexicans standing underneath, shooting at the American eagle perched on the top of the cross like a reprise of the Roman Empire. “I was his go-boy’ for this, go-boy for that,” recalled Kadish in the 1992 interview.2

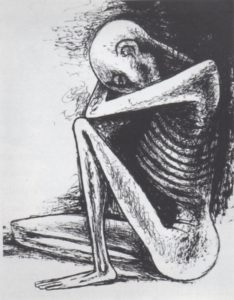

Fig. 2, Reuben Kadish (American, 1913-1992) Destitute, n.d. Life Collection of Art from WWII, #434 Photograph courtesy of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Those coincidental factors led to a tremendous opportunity for the young artists since Siqueiros had secured a major mural commission in Morelia, Mexico, and had intended to take on the project himself, according to recollections of Kadish. But Siqueiros’s energies were drawn to Europe by the Spanish Republican movement and the nascent Spanish Civil War. He fought on the side of the anti-fascists for three years. It was after seeing photos the Americans had sent him of a completed mural project for a workers’ community center in Los Angeles that Siqueiros invited his young charges to the University of Michoacan in southwestern Mexico, the former summer palace of Emperor Maximilian, to paint what ultimately became a 1,024 square foot mural executed in fresco style. “So we dumb Americans went off into the country and we painted a mural there,” recounted Kadish.3

Their mutual friend, the poet and budding art critic Jules Langsner, accompanied the young men to Mexico, their first venture outside the United States. Kadish, at age 21, and Goldstein, at age 22, literally became instant art stars once the U.S. press got wind of their politically charged mural. The stunningly ambitious composition of 1934, provocatively titled Struggle Against War and Terror, encompassed both Renaissance and Surrealist influences, complete with dangerous looking hooded figures strongly reminiscent of Ku Klux Klan thugs and their forebears from the Spanish Inquisition. Profiled in a splashy, two-page spread in Time Magazine on April 1, 1935, “On a Mexican Wall, Philip Goldstein and Reuben Kadish,” shortly after the mural was completed, the article quoted Siqueiros: “it is my honest belief that Goldstein (Guston) and Kadish are the most promising painters in either the U.S. or Mexico.

Kadish and Goldstein returned to the U.S. and joined the fledgling artistic arm of the Works Progress Administration. They painted another politically charged mural (restored in 1998) in 1935-36 at the City of Hope Tuberculosis Center in Duarte, California. But that proved to be the end of their short-lived yet remarkable partnership. The two split up after that, with Guston moving to New York and Kadish to San Francisco. “I got a mural to do there,” recounted Kadish, “and Phil went to New York, which was unfortunate; I thought we could have developed something in California. But every opportunity that I have had since that time I went to New York (as a young man), I felt that was where the thing was going to be, the place that an artist should go and develop.4

So striking out on his own as a WPA artist during the Great Depression, Kadish executed the brilliant and still extant A Dissertation on Alchemy mural in the Chemistry Building at San Francisco State College, completed in August 1937. It proved to be his sole San Francisco commission despite submitting twenty-six designs to the bureaucratically stuffy and decidedly conservative WPA. They were too flamboyant, too revolutionary, too this, too that.” recalled Kadish, somewhat bitterly, about his rejected designs in the Archives of American Art interview’. He also recounted a letter from a disgruntled Washington official who had dismissed one of his mural designs as “the kind of art Americans shouldn’t see.”6 These early experiences pushing big ideas and encountering stiff opposition and even rejection, forged his lifelong contrariness to following the path of least resistance.

Telling Kadish’s life story, even in Cliff Notes form, helps the viewer to fathom some of his epic journey to sculpture and a ferocious body of work in terracotta and bronze as uncompromising as any of the postwar’s best known sculptors. Picking up that story line again, during WWII, Kadish worked as a civilian for Bethlehem Steel and the shipping industry, building destroyers and submarines until he was recruited to join the U.S. Army’s Artist Unit, an elite branch funded by Congress to document the war effort. Many of his searing images of bombed out villages in Burma and India and heart-wrenching scenes of death and starvation are now in the collection of the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C. “I was interested in documenting what I thought was at that particular time the important part of what was going on there.” said Kadish. “And the famine was one part of it, and a very poorly trained Chinese Army was another part of it.”7

The brutal images he drew of emaciated figures (fig. 2) and skeletal-like corpses occupying the devastated and scarred streets of Calcutta carried the expressionist flame that Kadish kindled and kept burning throughout his long career. The horrific imagery from South India stayed deep in his psyche, eventually coming out decades later with his Roman-like cast of terracotta and bronze heads that were also based in part on the conflagration of Hiroshima and the mind-numbing statistic of 150,000 killed. “Nor so much Hiroshima as a place,” said Kadish in an interview with this writer shortly after the series took roots in the mid-1980s,”but as an idea.”8

But the earth-shaking events of WWII and his brush with the brutal exoticism of Asia had another impact on Kadish, back in the U.S. with a young family and no job prospects, so to speak. He finally made his move back to the east coast and the siren call of New York City. For a while, he worked for 25 cents per impression in a part-time job for Stanley Hayter’s storied Atelier 17 in Greenwich Village, printing editions for the likes of Joan Miro, Andre Masson, and other European Surrealists who found sanctuary in America. Keen on living in New York (a dream he harbored ever since his first boyhood visit there in the mid-1920s when he saw a shockingly explicit Courbet nude at The Metropolitan Museum of Art), Kadish longed to join old friends like Jackson Pollock who were migrating to the eastern end of Long Island for cheap housing.

But in 1945-46, with a growing family of his own, Kadish had no luck house-hunting there and eventually found a run-down 40 acre farm in Vernon, New Jersey, about sixty miles from Manhattan. For mostly economic reasons, he more or less turned his back on the percolating New York art world and became, in short order, a successful dairy farmer. “I got involved with animals,” said Kadish in an interview with this writer in the mid-1980s, “and was no longer able to give time to painting.”9 In the 1992 interview, the artist characterized that move: “Unfortunately I couldn’t find a place to live in New York, so I moved our to the country, New Jersey, and lost and separated myself. I could have been in Kansas. I think it was one of the really major mistakes in my life.”10 Though he grew enamored of the land and life cycles of raising animals, misfortune (or providence) pursued him. A catastrophic fire in his quonset-hut studio on the farm in the early 1950s destroyed all but a handful of his Abstract Expressionist styled oeuvre of paintings. Redolent with churning surfaces, some rough to the touch with a mix of sand and oil paint, the canvases were densely marked and cross-hatched in blazing hues resembling hieroglyphic-like symbols. He would never paint again.

But even that story leaves a tantalizing question mark since Kadish’s oldest son Dan, a painter in his own right, couldn’t endorse the story about the origins of the fire and believes to this day that it was more of an emotional conflagration of the artist deliberately destroying his own work. The son also recalls, as a teenager in the early 1950s, spending long hours with his younger brother Ken (now deceased) in the backwoods of the farm, helping their father dig trenches in the rich earth. “We began to fill them up with field stones and concrete: recalled Kadish during several interviews with this writer from his home in Vernon, the same farm his father once tended. He believes these were the very earliest of experimental sculptures, still buried and unmarked as some still undiscovered archeological wonder.

So after several years of existential torment from his profound loss, Reuben Kadish slowly developed a new sculptural vocabulary, first turning to the medium of clay and directly carving into the pliable material with the sharpened point of a pig’s rib from an animal he had raised and slaughtered for the family table.

“I woke up one merry day;’ recalled Kadish during a studio interview with this writer, “and realized many of my drawings were meant for sculpture and decided to turn them into three dimensions. 11 Kadish expanded on those early glimmerings about his metamorphosis to sculpture.”I believe that much of my work was done on impulse,” said Kadish during the 1992 interview, “because I felt that this was a feeling that I couldn’t put my finger on, and I impulsively would allow a piece of clay to go in a certain direction—I intentionally used clay (fig. 3) because it was God’s way of making the creatures on this world. In almost every society you had to have clay before you could even have a blade of grass or a tree to grow.12 The terracotta he used is the oldest of art materials and forms the mythic bond between antiquity, which he studied and revered, and the contemporary world.

Fig. 3, Reuben Kadish (American, 1913-1992) Nagasaki, 1986 Terracotta, 18 inches, Photograph courtesy of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Bronze casts (fig. 4) from the original terracottas would follow, also steeped in the ancient craft of lost-wax casting, pursued at a time when most sculptors were scavenging the mean streets of Manhattan for found objects or welding steel.

Once that dramatic transformation was made in the mid-1950s, there was no turning back, and Kadish moved his family back to New York City, selling his farm equipment, renting out his land to tenant farmers and starting a new career as a teacher. He taught design at the Newark School of Fine Art and Industrial Design, the Brooklyn Museum of Art School, and finally in 1960, began his long association with the Cooper Union in Manhattan as a professor of art history and sculpture. Setting himself up in a small carriage house on East 9th Street, walking distance from Cooper, the new empire included a nasty, rat-domiciled basement where his etching press was set up and where he would produce a blazing array of figurative-styled imagery, closely related to his sculptural oeuvre.

So Kadish, after a ten-year exile, returned to the then booming New York School scene that still championed Abstract Expressionist painting yet largely ignored sculpture, except, say, for the legendary likes of David Smith. He was fond of recounting to this writer the gist of the apocryphal dig from Franz Kline about Kadish’s newly adopted medium, “sculpture is something you bump into on the way to viewing a painting.” Kadish also began a long association with the Modern Art Foundry in Long Island City and fine tuned his lost-wax casting technique with the help of sculptor Fred Farr, a technical guru for Kadish’s move to bronze.”Most of my pieces,” recounted Kadish to this writer, “are nor fluid. There’s a lot of noise going on beneath the surface.”13

Fig. 4, Reuben Kadish (American, 1913-1992) Head, 1966, Bronze, 16 x 16 x 14 inches, Photograph courtesy of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

When he came out of his Rip van Winkle limbo in Vernon, almost three decades before his final series of Memorial heads, Kadish began exhibiting in the downtown terrain of the local, mostly artist run, cooperative galleries of East 10th Street, then Mecca for the jazz-influenced breed of independent artists, toughened by the Great Depression and WWII. That ‘noise’ he talked about was picked up years later by the late and influential art critic Thomas B. Hess writing in Portfolio, the hardcover Art News Annual in the fall of 1959. Hess selected Kadish as one of the “lesser known of American sculptural talents… Kadish seizes the throat of the contemporary reality without style, without pretense. This is it.” That same year, Kadish exhibited in the 5th Sao Paulo Biennale in the high-flying company of David Smith, Philip Guston and Robert Rauschenberg, as well as others. He was also invited to participate in the New Sculpture Group annual exhibitions held at the Stable Gallery and elsewhere. Chosen by his peers, Kadish’s long exile from the art world ended.

Even today, Kadish’s singular expressionism doesn’t look right to some tastemakers and seems to come from another time. But as his close and late friend, the painter Herman Cherry, said of his work, “Like Rodin, he’s always out of whack with the times:’ Indeed, Kadish harbors a passion for cultural anthropology, the bulging figure of the Venus of Willendorf (circa 15,000-10,000 B.C.) and her ivory-coated sister, the “Venus” of Lespugue. He uses archaic Greek and Egyptian myths and tempers them with Hebraic wisdom, from his one-of-a-kind bronze, Wandering Oedipus from circa 1962, to the grieving Demeter (Earth Mother I) in terracotta from circa 1968. Its a pantheon most twenty-first century mortals have lost touch with. The fantastic stories, incredible passions, and tragedies that cling to their names fit seamlessly into Kadish’s world. Earth goddess Isis, for example, is a crucial figure for the artist. The attributes of Demeter, goddess of the crops and devoted mother, meets the dropout farmer and family man Kadish head on. Just as in the female statuettes of clay from the 6th millennium B.C., Kadish exaggerates the female form, endowing her with mountainous breasts and a hilly pubis to celebrate her fecundity and life affirming power.

That work takes a decidedly new direction with his final body of work, the terracotta and bronze Memorial heads of the mid-1980s, moodily darker yet convincingly mortal. In this knobby-headed cast of characters, with their mottled cheeks, chewed lips and swollen eyes, Kadish’s expressionist vocabulary erupts with a pent up vengeance. They were inspired, according to the artist, by the 40′ anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Portrait of the Artist carries a high-decibel charge, a lava-like surge of rutted surfaces in seemingly untranslatable code, a kind of apocalyptic hieroglyphic that becomes the artist’s new scripture for a post-atomic world. Though distorted almost to Bacon-esque proportions, Portrait of the Artist bears a startling resemblance to the aging and seriously ill Kadish, as if he had transmogrified into another type of creature—inquisitive, penetrating, and yet dramatically comic. Dream, a closely related—at least in spirit—work from the same series, executed in both terracotta and cast bronze form, exudes a tribal expression, something dug from the earth after eons of undisturbed sleep. The bulging closed eyelids, the full, slightly open lips, as if eternally parched for some liquid, appear ancient yet crazily contemporary, a melded concoction of funerary portraiture grafted to both German Expressionist and Surrealist roots.

Curiously, the terracotta itself is fragile, not combat-ready like the bronzes. When first made in the big, gas fired kiln at Cooper Union, the odds were high that some of the heads might fall off of their temporary pedestals as they dried, changed color and hardened as they pleased, prey to the heat and humidity, but most of all to the initial pressure of the artist’s powerful fingers. They might also explode in the process due to small pockets of air or impurities in the clay. They are fragile yet contain the potential to last through millennia. The heads, numbering no more than half a dozen characters, including Portrait of the Artist, bear an eerie resemblance to the terracotta effigies excavated at the ancient site of Sao in Chad. But the cool and colossal marble head of the Roman emperor Constantine at The Metropolitan Museum of Art exerts an equal influence over Kadish’s army of portrait heads. The incendiary mixture of emotion and intelligence fires the artist’s vision just as the strong features and piercing gaze of the proud Roman speak loudly of the power of Imperial Rome. But Kadish’s men have lost their hubris. Their empire is melted, a smoldering graveyard. As though aware of their war ravaged ancestors, these contemporary heads look out, startled, atom-shocked and unmistakably world weary.

Though hobbled and left out by long periods of exhibition inactivity, Kadish hammered out a credible exhibition career. It included stints with the Elaine Poindexter, James Graham, and Grace Borgenicht galleries, as well as two retrospective/survey exhibitions during his lifetime at the now shuttered Artists’ Choice Museum in SoHo (1985) and the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton (1990). Yet, for a bewildering variety of reasons, some a result of his decidedly prickly manner and general contempt for most commercial art dealers, Kadish never made it as an art world star, like his friend Pollock. He made a far larger impact though on a generation of art students who passed through the great hall of Cooper Union. Those lucky ones heard Kadish’s thundering lectures on Egyptian funerary sculpture and Greek mythology, accompanied by cinema-like slide shows of exotic art and architecture from around the world. Even during his final, productive period of the mid-to-late 1980s, most attention from critics, art historians and filmmakers were centered not on Kadish’s art works or accomplishments but his raconteur-like recollections of the deified Jackson Pollock or his personal brushes with Siqueiros and other artist titans like Joan Miro.

Kadish and his wife Barbara even turn up as minor characters in Pollock, the Hollywood-style film about the artist’s life and work from 2000, starring Ed Harris. Kadish is portrayed there in a negative light, a conspiratorial drinking buddy of Pollock’s who was shooed away by the protective artist-wife, Lee Krasner. Hardly anybody gets it right about the amazing time that Kadish lived. ‘Artists of my generation,” said Kadish, “didn’t have a specific direction. European artists on the other hand had a pre-destination. In America, we never know exactly what an artist was supposed to do.”14 Kadish found his way, and that remarkable journey will be preserved in works like Portrait of the Artist, for others to learn from and become enriched by.”15

Notes

1 Stephen Polcari, Interview with Reuben Kadish, April 1992, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (hereafter cited as Polcari).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Judd Tully, studio interview with the artist, April 1985 (hereafter cited as Tully).

9 Ibid.

10 Polcari .

11 Tully.

12 Polcari.

13 Tully.

14 Tully.

15 For more information on Kadish website, visit: reubenkadish.org