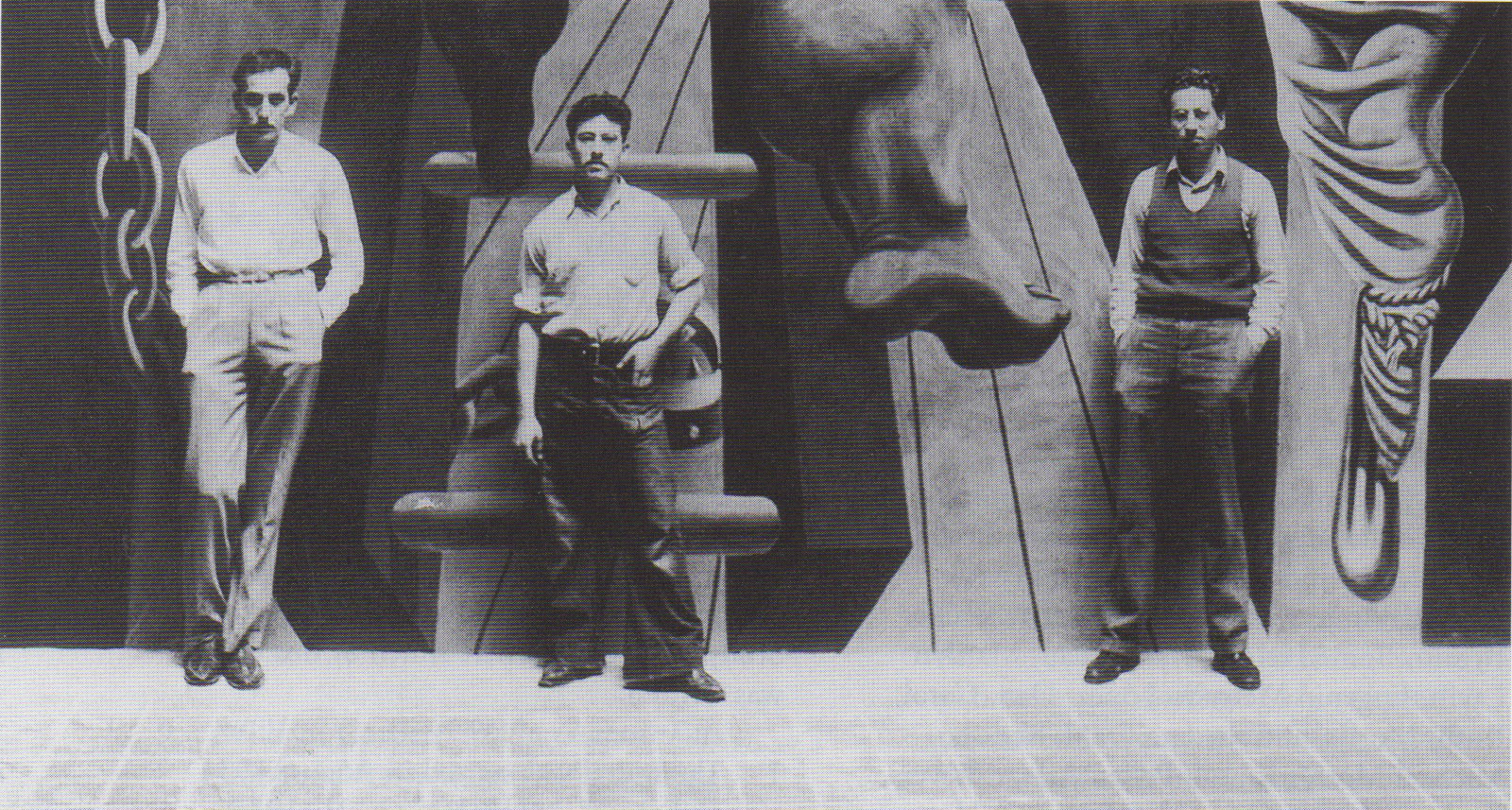

(from L to R) Philip Guston, Rueben Kadish and Jules Langner on location at the mural “The Struggle Against Terrorism,” Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico in 1935

Michoacan, on the Pacific Ocean, is one of the least known of Mexico’s 28 states. Yet there is hardly a Mexican schoolboy who is not familiar, for one reason or another, with Morelia, its capital city. There 152 years ago was born Don Agustin de Iturbide. Not even a name north of the Rio Grande, Don Iturbide was a minor Mussolini 100 years ahead of his time. He became dictator of Mexico, was proclaimed Emperor Agustin I only one year after the last Spanish viceroy was driven out. Emperor Agustin reigned for only one winter, left for Europe, returned and was executed. So, 43 years later, was Mexico’s Third Emperor, fluffy-whiskered Maximilian. Tragic Maximilian chose Morelia as the site for a summer palace. The building still exists as a museum administered by the state university, San Nicolas de Hidalgo de Michoacan. Last week Maximilian’s old palace provided Mexican schoolboys with one more reason for being conscious of Morelia. In that hot little place black-coated government employees and peasants in straw sombreros gazed in open-mouthed wonder at one of the biggest, most effective frescoes in all Mexico, painted not by one of Mexico’s famed group of revolutionary muralists, but by a pair of young, talented, enthusiastic U. S. citizens from Los Angeles.

The project was started last summer when authorities in Michoacan’s state university realized that they had in their museum a huge wall, unbroken except for one small balcony. To Mexican eyes this bare space cried aloud for a great mural such as decorates the main public buildings in Mexico City.

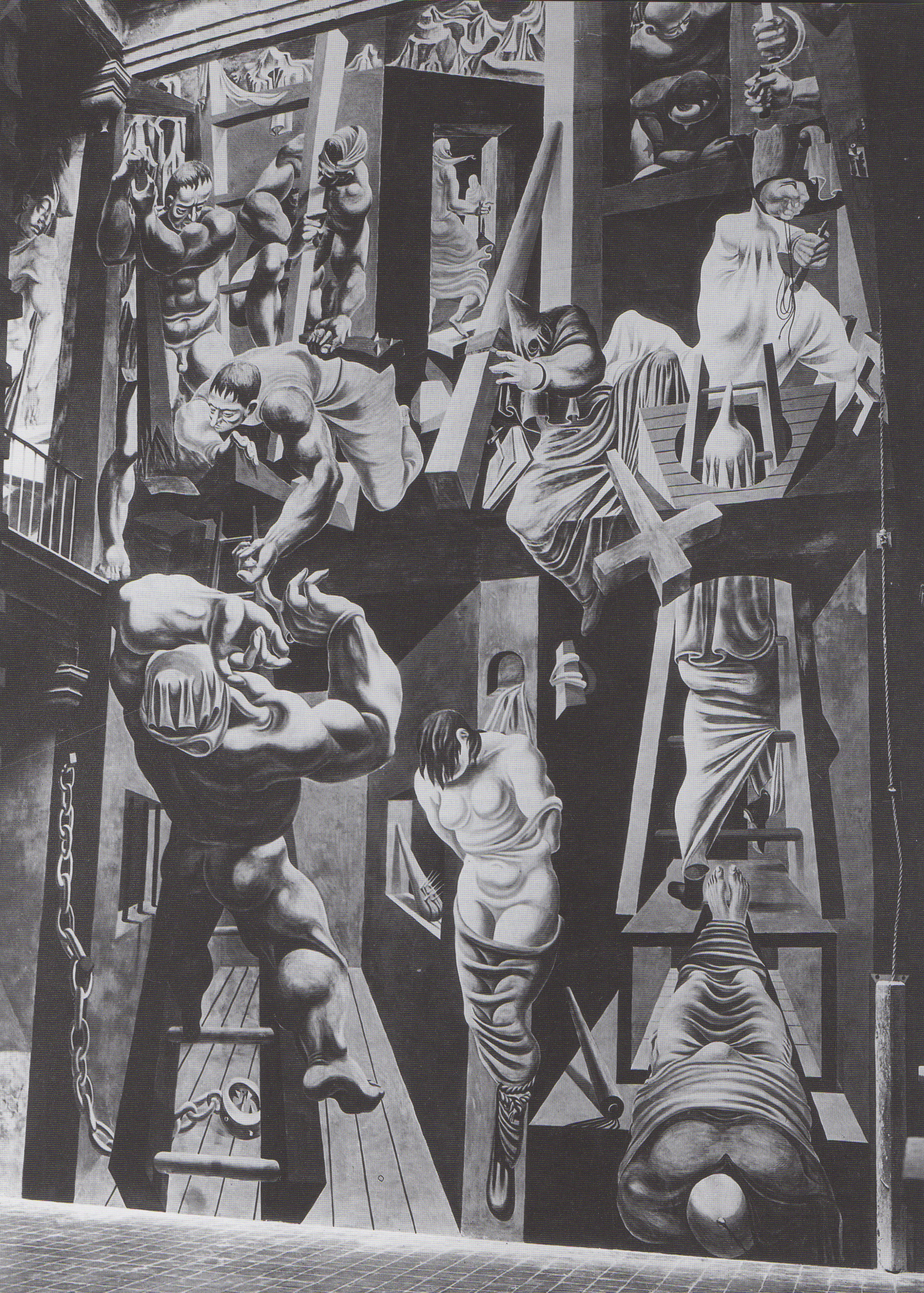

Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner, “The Struggle Against Terrorism,” 1934-35, center section of fresco at the Museo Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico, 40 ft high. Photograph taken in 1935, probably by Casa Lopez Articlos Fotographicos Revelado Imppresion y Amplification, Morelia, courtesy Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Diego Rivera was busy at the Federal Capital finishing a paraphrase of his fresco which the Rockefellers ordered out of Manhattan’s Radio City (TIME, May 22, 1933, et seq.). Muralist Orozco was tied up with a “proletarian mural” for Mexico City’s Palace of Fine Arts. Painters Pablo O’Higgins and David Alfaro Siqueiros persuaded the Michoacan University trustees to give this great opportunity to two young men one of whom had helped Siqueiros finish a fine fresco in the Workers’ Cultural Center in Los Angeles two years before: Reuben Kadish, 21, and Philip Goldstein, 22.

Spectacled Muralist Kadish and dapper Muralist Goldstein are both parlor pinks and both influenced by a Los Angeles esthete known as Lorser Feitelson. An able draughtsman with a shrewd eye for publicity, Artist Feitelson was anxiously trying to burst into the news last week as the prophet of a new art movement called Post-Surrealism or New Classicism. As an example of his new school’s work he presented his own canvas entitled Genesis. Similar to fresco painting in technique, it showed a young lady’s rear, her navel reflected in a mirror, a rising sun, an egg, half an avocado pear. Attempting to explain the difference between this and old style Surrealism, Artist Lorser Feitelson wrote:

“The New Classicism is the antithesis of the esthetically irrelevant psychological illustration of the popular Expressionist-Surrealists and should in no way be identified with their dadaistic denial of the universality of the esthetic. The graphic objectification of the conscious and subconscious psychic meanderings in itself does not create art. . . . Thus in Genesis, the contemplation of the direction and sequence of the introspectively associated objects dictates the rhythms, which are ‘thought-unity’ rhythms rather than graphic lines.”

Fortunately Reuben Radish and Philip Goldstein took nothing but their technique from New Classicist Feitelson. The impoverished Michoacan University announced that it could afford to pay the painters’ living expenses for only six months. Kadish & Goldstein jumped at the chance, packed up for distant, dusty Michoacan, rolled up their sleeves and with only one assistant, 23-year-old “Itinerant Poet” J. H. Langsner, painted 1,024 sq. ft. of true fresco in the required 180 days.

Working like beavers, neither could claim any single figure as his own. The huge wall, when finished, showed with gripping realism dear to the Mexican heart the Workers’ Struggle for Liberty. The left half of the main wall depicted nude workers knocking from a ladder, with splintered beam, lead pipe, and spike-studded stick, a colossal figure supposed to represent the Medieval Inquisition. So shrewdly foreshortened is this last figure that it seems to be crashing right out of the wail down on spectators. In the centre is the broken-necked body of a hanged woman and above her a hooded and villainous priest. The other half of the wall is given over to the Modern Inquisition. Near the floor is the body of an electrocuted man, realistically rigid. Rising through a trap door are two hooded figures representing the Ku Klux Klan and Naziism. In the extreme upper right, Communists with sickle & hammer are rushing to the rescue. Crowed Patron-Discoverer David Alfaro Siqueiros last week: “It is my honest belief that Goldstein & Kadish are the most promising young painters in either the U. S. or Mexico.”