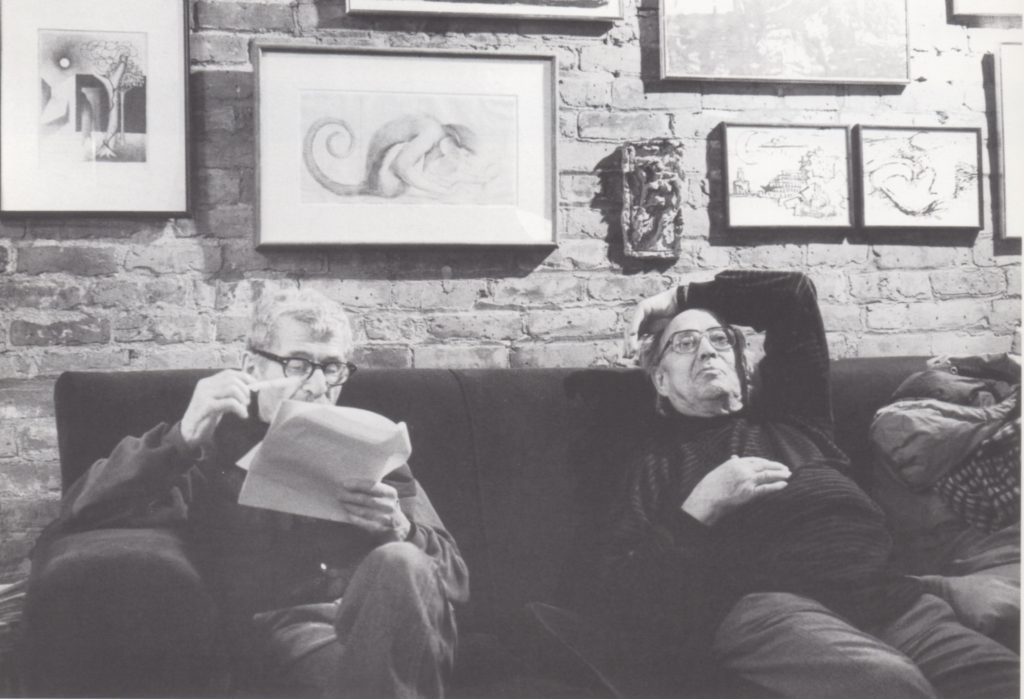

Reuben Kadish (right) in his 9th Street studio, listening to Herman Cherry (left) read his essay for the catalogue of Kadish’s 1990 retrospective exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum. Photograph: Regina Cherry

Around 1932 or 1933, in Hollywood, California, Lorser Feitelson, a painter well known for his knowledge of Renaissance art and a teacher of Reuben Kadish, then twenty years old, brought Reuben and Philip Guston to the Stanley Rose Bookshop, where I worked. I had just opened a modest art gallery on a balcony in the rear of the shop. As I myself was barely out of art school, I had been searching for young artists and had heard of Reuben and Philip as promising young painters. In 1930 Reuben had entered the Otis Art Institute, where he met Philip Guston. Both being political mavericks, they soon found themselves at odds with the county school. In about 1931, Reuben entered Los Angeles City College for a year to study anthropology and zoology. That interest would continue throughout his life.

Alfaro Siqueiros, the dynamic Mexican muralist who had come to L.A. in 1933 to teach at the Chouinard Art School, was to paint a controversial fresco in the Plaza Art Center in downtown L.A., thus attracting Reuben who became his assistant. In 1935, Siqueiros was to be instrumental in getting Kadish and Guston wall space in the University of Michoacan, Morelia, Mexico. An article in Time Magazine featured them as the most promising young painters in America.

After their exhibition at Stanley Rose Gallery, I saw Reuben and Philip infrequently. They had ended their collaboration, Philip to go to New York and greater success and Reuben to execute a mural commission for the W.P.A. on the subject of alchemy. The Depression was in full swing. War rumblings were heard in Europe.

With the slow demise of the Project, beginning in 1940 Reuben would work as a copper-smith for the Bethlehem Steel Yards on the docks of San Francisco. By 1936 Reuben had crisscrossed America from San Francisco to New York many times and had felt the rapid pulse and energy awakening in art as from a long sleep. The art world of America was opening its eyes. Young talents, Isamu Noguchi, Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, David Smith, and those not yet on the horizon, confirmed what he had already felt — New York was becoming the seedbed for a cultural revival. On one of his visits, Reuben had met the artist immigrants from Europe who were exerting an influence on the New York scene.

The few years of development under the sponsorship of the government began to bear fruit. The artists had found their own voice — an uninterrupted period of painting had con-solidated their position as a force on the cultural map of the country. A small, discerning public had followed in its wake, broadening the base for the artists to move in. The young, intense painters and sculptors were waiting in the wings, talking-talking-drinking-drinking and paint-ing in a frenzy of newly found discovery. The sense of inferiority vis-a-vis Europe was slowly beginning to fade. The stranglehold held by European artists and Paris had been broken. Artists from far and wide were moving to New York as if drawn by a magnet. to weld an art community that would shift the center from Paris to New York.

Historical events had caught up with Reuben. In 1943, a message from the War Department asking Kadish to join the Army Artists Unit to document the ongoing theaters of war, however, delayed his move. He was assigned to India, Burma and other Eastern war zones, and his assignment had a shattering effect on his life. The conditions of depravity among human beings in what seemed a senseless war, the stalking death, the indignities of shattered bodies, the bombings and human debris — what could all this inhumanity mean? How could one ex-press it? It was a message that fought to get out. Reuben’s war drawings are some of the most powerful and agonized he made. It took a while for him to record them on paper. The flesh was too fresh.

The year 1945 was crucial for Reuben. The experiences of the war and the final decision to move to New York with the family came with the conviction that an artist should be in the eye of the storm. Besides, he had many friends who would open doors for him. Bill Hayter’s Atelier 17, where he had worked, moved from San Francisco to New York, and Reuben continued to print his work as well as printing Miro’s and Pollock’s etchings. Once settled in New York, Reuben and Jackson Pollock decided to look for a summer place. Since some of their friends had moved to East Hampton, within commuting distance, they went to look around. In the Springs, close to East Hampton, they found cheap fishermen’s shacks. On one visit to Harold Rosenberg’s (the art critic who coined the term Action Painting for what would be known as Abstract Expressionism) in the Springs, Jackson and Reuben repaired Rosenberg’s caved-in roof. Jackson had bought an old house with a magnificent view of Accabonac harbor. It was quiet and beautiful and spoke of other times. Reuben had no such luck: with a family of five he needed larger space and went elsewhere to look.

After a time, Kadish found a place in Vernon, New Jersey, sixty miles from New York. It was dairy farm country, and he bought a dairy farm. He became a dairy farmer for ten years. Why a dairy farmer? I have not been able to get a reasonable answer from him that explains why he derailed his talent during these years, why he dropped completely out of the art world.

Had Reuben, after so many years as a painter, lost touch with himself and with the inner struggles that had given him so much joy and pain and so much fulfillment? What could take its place? It is my opinion that Reuben used the farm years to reconsider his position. His drawings and paintings had been biased toward volumetric form. His feeling for form was three dimensional, and he had a natural affinity for materials. Reuben’s factory work during the war may have unknowingly contributed to it. David Smith always spoke of his factory work as a master welder in Schenectady making Sherman tanks during the war.

Dairy farming was back breaking work, but in his spare time Reuben worked on some drawings. In other words, he kept his hands in. After five years he broke the mold and made his first terra cotta — a small nude. It would be five more years before he would give up farm-ing permanently to devote himself fully to sculpture. The border had been crossed; the struggle was over, a new one to begin. It is a curious fact that I have noticed — that many sculptors start as painters. I will mention two of note: David Smith and Xavier Gonzales. It is rare to see a sculptor turn painter.

Reuben’s experience in India had etched the mythic-religious-sensuous art into his consciousness. The earthbound quality of these art forms, their relationship to nature and to man, the earth mothers and bestiaries entwined with myths and his own sensuous nature combin-ed to give his own art an authenticity difficult for a sophisticated man to achieve. As in other countries with a pre-historic past, animals share a great portion of myths and history. Reuben had mentioned animals to me in a special way, but I had not picked up on it. Now I did. He answered me flippantly, “I like the warmth of pigs,” slyly looking at me (he had raised them for food), “furry animals,” and he added that “horned toads had a special place in my youth.” Flippant or not, they relate to his sculpture: animals remain a great source of imagery. There is an intertwining of animals and human beings. In his own myths, Reuben has built a sophisticated, primal art that transcends time, making it speak in the language of today.

In 1950 Reuben began making small clay sculptures. Working in clay was like touching earth. It was the mother, the giver of life, the source of being. The interim of silence had reawakened old loves. Reuben, a natural craftsman, had found his metier. His hands remind one of the series of hand studies by Picasso drawn in 1921, sensitive, clumsy, powerful. I have watched Reuben’s seeing, thinking fingers probing for the right form — while sketching in clay, digging the archaeology of the subconscious, the finger sprouting magically like a growing plant into a living image. It is his link with the immediacy of now and the milleniums past that collapses time.

Some of his large terra cottas look as if they had been dragged from the earth, bringing with them scriptural matter. Clods of earth cling like leeches to its life force. They become ornaments of raw beauty. The female figure assumes the “Da,” metaphor of mankind, the pre-historic earth goddess. Kadish’s experiences in India confirmed his philosophical and aesthetic tastes. The epic lushness of Indian art, the temples and monuments alive with snake pit writhings of its history and myths, the colorful frescoes and sensuous sculpture struck his archaeological and creative chords — the female figure as a hedonistic concept of birth and rebirth. It is interesting to note that the title for one sculpture, Queen of Darkness, Moloch II, a sacrificial queen, is also the name of an Australian spiny lizard. Architecture, animals, unidentifiable objects sometimes intrude on the figure or meld into forms. Jocasta III, Queen of Thebes, a Homeric character, joins both animal and human characteristics. Indira, Earth Mother II, fantasizes a series of sequential breasts bursting with voluptuous birth. Architecture abounds with humanoid elements.

In recent years, Reuben has been working on a series of oversized clay heads. Like all art of monumental force, they disturb and elevate, unveiling our fears and frailties. As in the Easter Island heads — their unseeing eyes forever seeking the horizon of endless seas — Reuben’s geological, glacial tattooing designs the faces like those of Maorian tribesmen; the corrosive surface bubbles and erupts. What was a symbol becomes abstraction. They are our dreams. When economics allow, Reuben casts them in bronze, that durable material that will outlive their myths.

Kadish has been teaching for over thirty years, the last twenty or so at Cooper Union, where his vast knowledge and encouragement have created a whole generation of sculptors and painters.

Kadish’s work in clay keeps him as close to the earth as he can get. His blunt capable fingers make the clay writhe with spontaneous life. Drawing was and is one of his first loves. Reuben never stopped drawing, not even during those desert years when his world had stopped. From his earliest Renaissance-like drawings while working on the murals, to his latest monotypes with their freedom of imagery and execution, he has developed a personal style that can only come with a mature, fermented vision. The medium of monotype itself demands a chancy execution where mistakes can be utilized, where possibilities are not programmed but accepted. The juices run free in a spontaneous gallop.

Until recently, Reuben and his wife, Barbara, plowed and worked a large garden of flowers and vegetables, which they canned for the winter and of which their friends became beneficiaries. He cannot keep his hands out of the earth. To this day, he still receives the year-book from the Department of Agriculture.

Kadish’s need and love of the earth are not unlike that of the Greek god Antaeus — son of Gaea, the earth mother — who became stronger each time he embraced the earth.