The story of Surrealism’s influence on American art is often boiled down to a three-man relay: Matta passed the torch of automatic painting to Arshile Gorky, who slipped it to Jackson Pollock, who raced across the finish line to Abstract Expressionism.

We all know things were more complicated. Just how much more is reflected in the closely packed expanses of “Surrealism USA,” the most ambitious exhibition to be seen at the National Academy Museum in some time. Those three gold medalists are here, along with many of their big-time confreres like Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, but so are scores of artists who are almost unknown now — and maybe always have been. If you leave this show disliking Surrealism American style, at least you’ll know why.

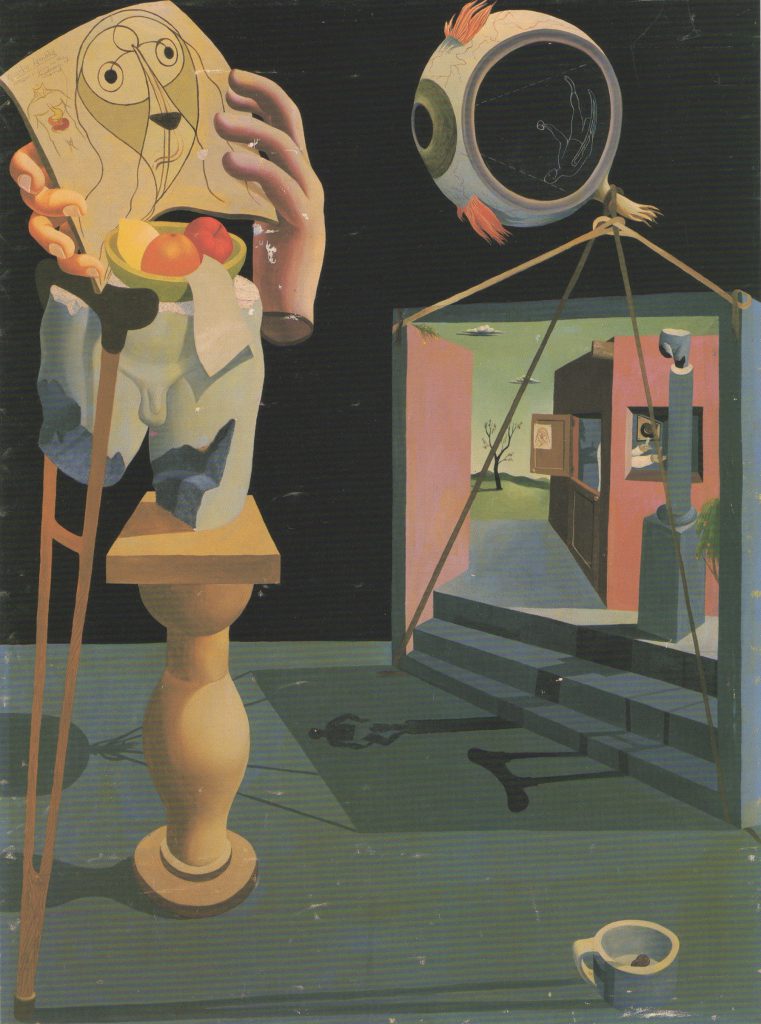

Reuben Kadish, Untitled (Dr. Entozoak), oil and mixed media on canvas, 48 x 36 inches, 1935

But “Surrealism USA” is not easy to dismiss. It is too informative, high-spirited and humbling. It reflects how much of the art of any period falls away, and suggests that while the original fullness can never be retrieved, art-historical diligence has its own rewards.

Such diligence has been pursued by Isabelle Dervaux, who left the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 2000 to become the National Academy Museum’s first curator of modern and contemporary art. The museum calls this show the most in-depth survey of American Surrealism since 1977.

There are some flaws and serious omissions, some because loans fell through. (Pavel Tchelitchew’s radiantly ghoulish “Hide-and-Seek,” from the Museum of Modern Art, and one of Ivan Albright’s clotted, teeming paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago will join the show when it goes to Phoenix.) But the assembled work still gives abundant evidence that Surrealism shook American art to its roots.

Ms. Dervaux has come up with 120 works spanning 1930 to the mid-50’s and representing more than 60 artists from across the United States (as well as the European Surrealists who spent time here); they fill five good-size galleries. She has included a lacy etching from 1949 by one Vera Berdich, an artist who taught at the Art Institute of Chicago. There is a small, shining abstraction by Charles Howard, who showed with Surrealism’s great New York dealer, Julien Levy. Its metallic bladelike forms stand apart from both the Abstract Expressionist and the realist works in the show’s biggest gallery.

While most of the works are two-dimensional, the show is sprinkled with unfamiliar sculptures — early, modestly earthbound pieces by Joseph Cornell, one by Isamu Noguchi that uses real bones — and is laid out with some fanciful curved walls, which add needed hanging space. The final gallery is festooned with string in homage to Duchamp’s installation of the 1942 “First Papers of Surrealism” exhibition in New York, organized by André Breton.

Surrealism may have unleashed the unconscious and made irrational juxtapositions de rigueur, but Ms. Dervaux keeps a close rein on things, proceeding in strict chronological fashion with stylistically coherent sections that show how making history needs company.

The show begins by reminding us that in the early 1930’s, long before Matta met Gorky, American artists flocked to Surrealism in droves, usually under the sway of the surgical precision of Salvador Dalí’s realism. They had seen Surrealist works in European magazines and art galleries. In New York, Levy exhibited Dalí’s “Persistence of Memory” in 1932 and gave the artist a solo show in 1934; later, Miró showed with the dealer Pierre Matisse on a regular basis. Also in 1934, Peter Blume’s mildly Surrealist “South of Scranton,” on view here, caused a scandal when it won first prize at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh.

But by the end of 1936, Surrealism was entering the museum establishment. That’s when Alfred Barr’s 600-work exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism,” the first large survey, opened at the Museum of Modern Art.

The initial gravitation toward Dalí produced unusual hybrids. Social Realism and American Scene Painting, in particular, needed only slight adjustments to become strange. Sometimes the adjustments seem almost pasted on. Remove the Dalíesque props from Malcolm Roberts’s “Deserted Landscape,” and what remains is a generic dust bowl farm scene. Things are more organically fused in Alexandre Hogue’s “Erosion No. 2 — Mother Earth Laid Bare,” where furrows of barren farmland are reshaped into a flattened, exhausted nude and the kitschy earnestness may make you laugh.

Other artists ratcheted up Dalí’s illusionism to a squeaky cartoonishness, as Blume did in his virulent “Eternal City” (1934-37), which is presided over by a manic, green jack-in-the-box caricature of Mussolini. Blume wasn’t the only American locating Surreal moments of irrationality in society itself, rather than in the imagination. Implied or outright violence dominates the bronze reliefs of David Smith’s “Medals for Dishonor” and James Guy’s painting “Police (Public Servants).” Walter Quirt’s 1935 canvas “The Future Is Ours” recasts a group of American farmers, sailors and soldiers as menacing xenophobes and gives its famous title a selfish ring that resonates today.

An exception was Boris Margo, who began to push Dalí’s realism toward all-over abstraction, albeit one populated by strange little creatures, as early as 1935. His bizarre “Portrait of My Mother” suggests a post-nuclear sunset rendered by Tiepolo.

The show devotes a section to the California Post-Surrealists, nearly a dozen painters centered in Los Angeles who were the only American artists to organize a formal Surrealist group. A certain serenity is the rule here. The young Philip Guston and Reuben Kadish borrowed from De Chirico. Helen Lundberg, a leader of the group, perfected an ethereal symbolic realism that holds up well to Georgia O’Keeffe’s. Lucien Labaudt’s profusion of Classical forms, titled “Shampoo at Moss Beach,” has a painterly bravura that evokes, for what it’s worth, a tasteful Neo-Expressionism before the fact.

In the largest gallery, where the show reaches the 1940’s, Matta’s automatist torch is generously passed around. Its beneficiaries include Kurt Seligmann, Charles Seliger, and Enrico Donati, whose luminous “Lutins S’Aiment” of 1945, in which the paint is more wiped on than brushed, may be his best work.

A 1943 Pollock drip painting is flanked by similarly early swirls by Knud Merrild, a California Post-Surrealist, and Gerome Kamrowski, as well as an automatist painting on which Pollock, Kamrowski and William Baziotes collaborated in 1940-41. Kamrowski’s imposingly garrulous (and garrulously titled) grisaille canvas “Part I — The Great Invisibles: Script for an Impossible Documentary” of 1945 hangs nearby, hovering on the border between period piece and masterpiece.

But the show’s final sections also include works that blithely ignored Matta and Abstract Expressionism. One is a small painting by the continually overlooked George Ault; it depicts a plain and icy winter landscape occupied by a wonderful translucent vibrating orb, a bit of abstraction on the lam.

In the catalog Ms. Dervaux anoints Federico Castellon, whose work is seen in the first gallery, as Dalí’s most successful American follower. The distinction may better fit artists who came into their own later on, including a painter named Charles Rain, whose “Magic Hand” of 1949 has Dalí’s fiery light and creepy miniaturist intimacy. Or maybe the mantle should go to John Wilde, who turns 86 this year. His portraits here, “A Near Miss” and “Exhibiting the Weapon,” both from 1945, leaven Dalí’s hyperrealism with a slight primitivism and give their subjects flat monochrome grounds. They have a severe yet opulent eeriness.

The works by the European Surrealists — Yves Tanguy, André Masson, Max Ernst and, of course, Matta — are also often outstanding, and help clarify the great debt American art owes Surrealism. But they also seem a bit like onlookers in this vigorously illuminating show.