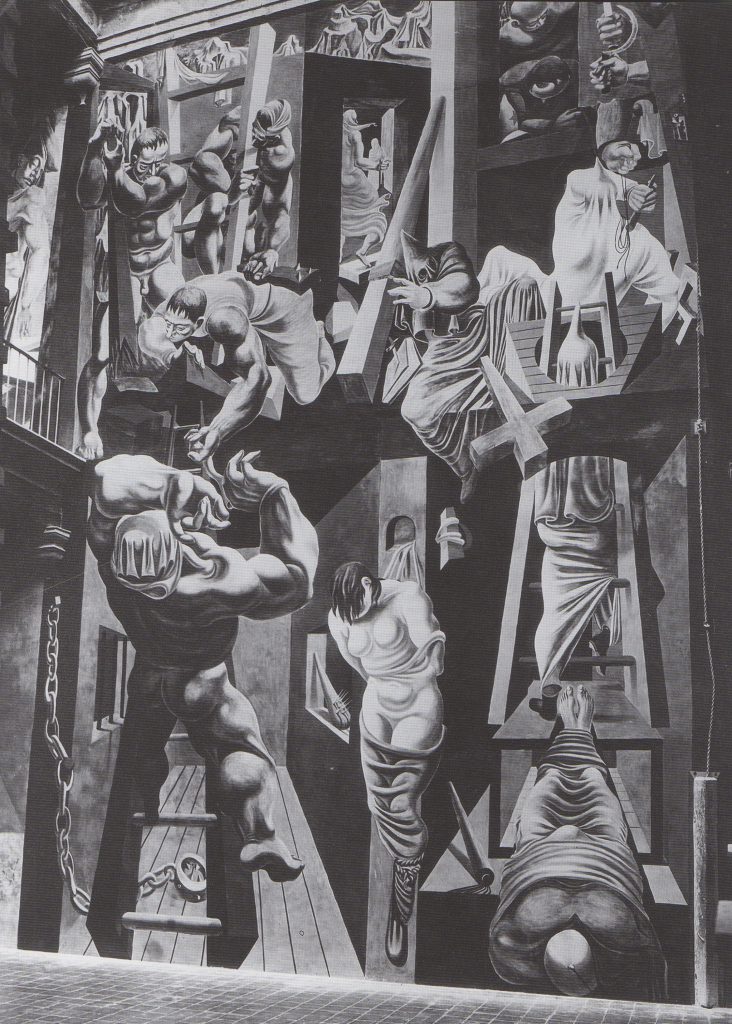

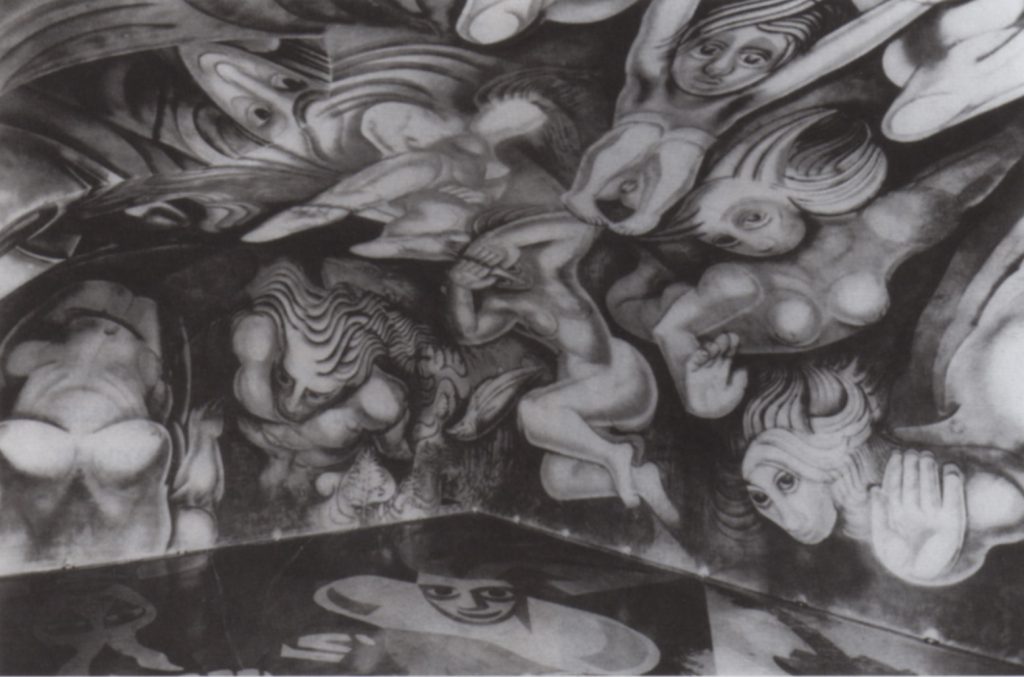

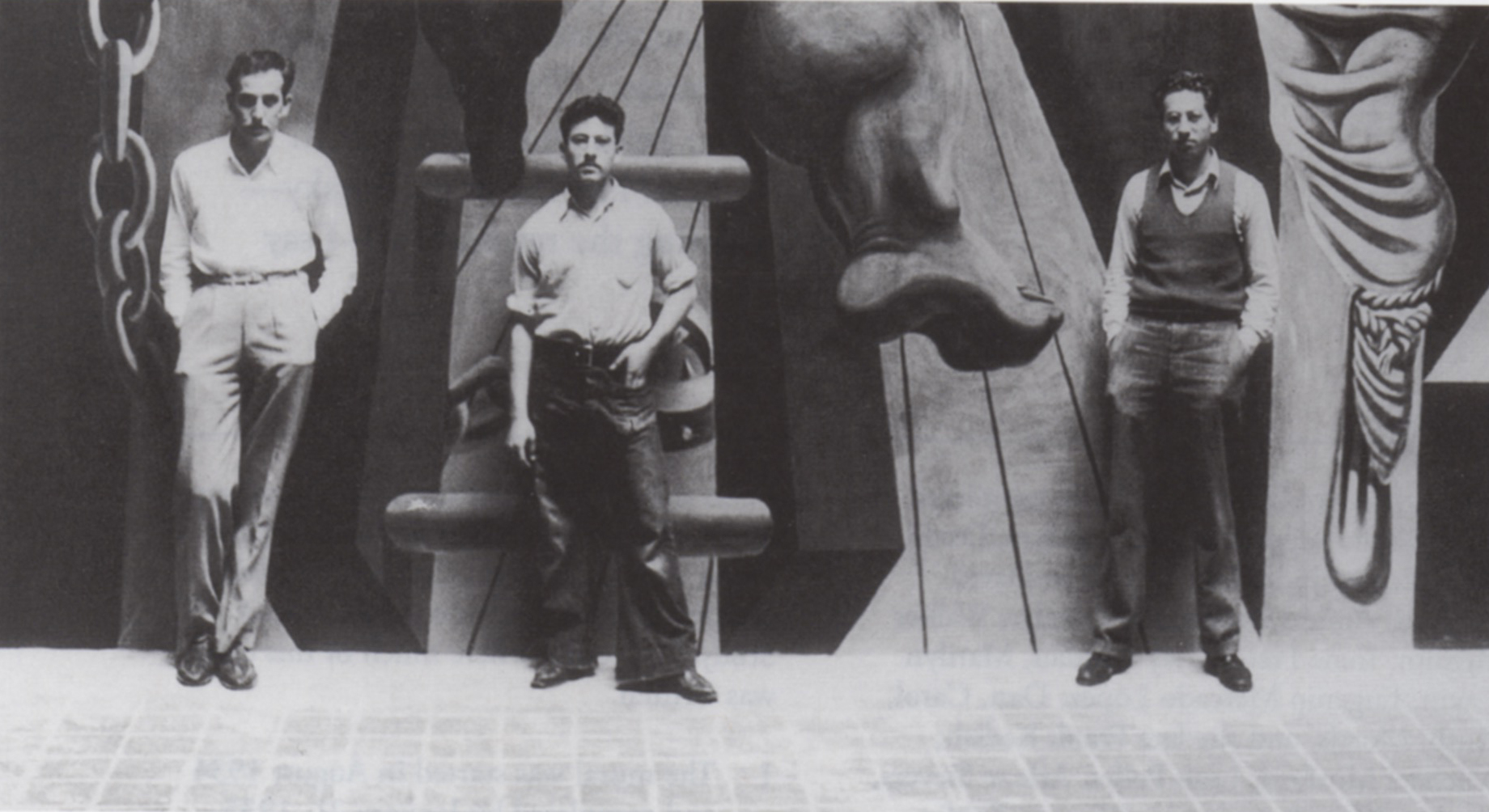

Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish (and Jules Langsner), The Struggle against Terrorism, 1934-35. Center section of fresco at the Museo Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico. 40 ft. high. Photo-graph taken in 1935, probably by Casa Lopez Articulos Foto-graficos Revelado Impresion y Amplification, Morelia, cour-tesy of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Sightseers touring the Museo Michoacano in Morelia, Mexico, a converted baroque palace where Emperor Maximilian once stayed briefly, often react with puzzlement when they come upon its most unusual feature, an epic 1930s mural (frontispiece) that decorates the wall of an interior patio. Of course, Mexico is renowned for its murals, especially those painted by the country’s famed revolutionary artists in the 1920s and 1930s. Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros are widely celebrated as Los Tres Grandes throughout the world. But the composition and subject matter of the Museo Michoacano mural, known variously as The Struggle

against Terrorism, The Struggle against War and Fascism, or The Inquisition, hardly appear Mexican in origin, subject, or style. The signatures of its artists, Phillip Goldstein and Reuben Kadish, and their assistant Jules Langsner strike no chord of recognition for most spectators, and their monumental work seems jarringly out of context in a museum of indigenous and Hispanic artifacts.

(fig. 1) Postcard showing main entrance of the Museo Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico. Estate of Philip Guston

How did such a design, by U.S. artists of no seemingly established repute, end up in this faraway place? Despite their wonderment over its origins, visitors who encounter this 1,024-square-foot saga, painted in 1934-35 and uncovered in 1973 after three decades hidden behind a fake wall, are typically riveted by the terrifying spectacle of race hatred and intolerance throughout the ages that unfolds before their eyes.1 Viewing the mural takes them on an abbreviated journey from biblical times through the Middle Ages and beyond, to the eras of the Ku Klux Klan and Adolf Hitler. What they see was considered important enough at the time of its completion to be described and partially illustrated in the respected U.S. newsweekly Time.

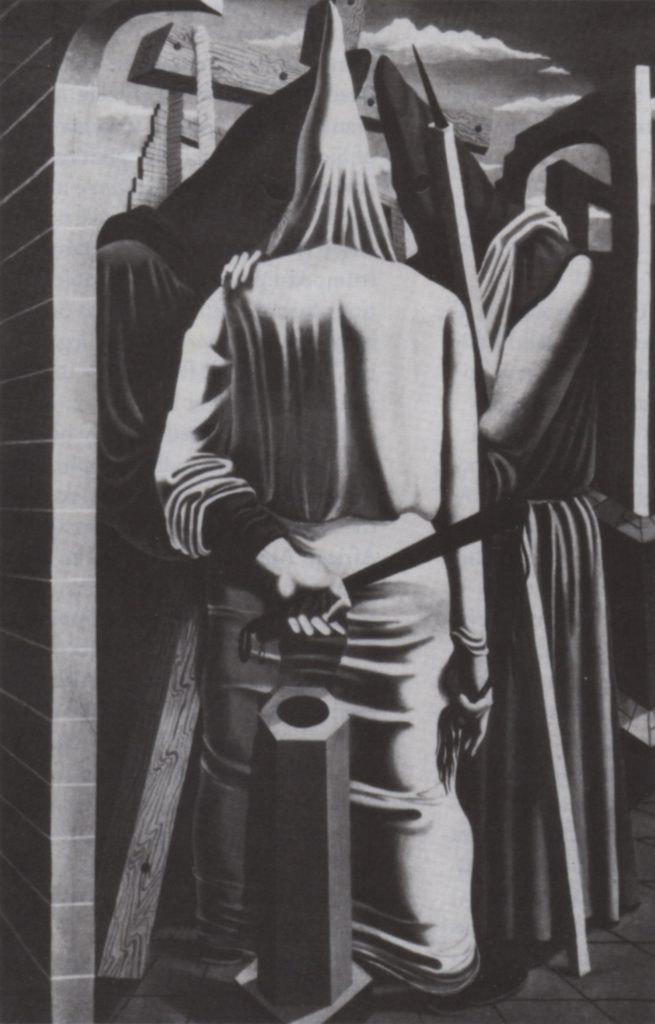

The writer for Time characterized the creators of this astounding fresco as a “spectacled” Kadish, twenty-one, and “dapper” Goldstein, twenty-two, recounting in some detail how this unlikely pair from Los Angeles had obtained the commission to decorate “the former summer palace of Emperor Maximilian” located in “one of the least known” of Mexico’s states (fig. 1). Their good fortune was credited primarily to support from the charismatic Siqueiros, with whom Kadish had previously worked on Tropical America, a controversial outdoor mural painted for folkloric Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles. Given the opportunity to paint “On a Mexican Wall,” as Time‘s head-line put it, Goldstein and Kadish demonstrated considerable skill,creating a series of colorful, oversized, fore-shortened muscular figures, positioned within a complicated architectural enframement. The mural’s protagonists appear ritualistically engaged in activities brutal, sinister, and xenophobic. According to Time (based on details provided by Langsner): ‘The left half of the main wall depict[s] nude workers knocking from a ladder, with splintered beam, lead pipe and spike-studded stick, a colossal figure supposed to represent the Medieval Inquisition. . . . In the centre is the broken-necked body of a hanged woman and above her a hooded and villainous priest. The other half of the wall is given over to the Modern Inquisition. Near the floor is the body of an electrocuted man, realistically rigid. Rising through a trap door are two hooded figures representing the Ku Klux Klan and Nazism. In the extreme upper right, Communists with sickle c hammer are rushing to the rescue.’

Neither expounded on nor illustrated in Time—or any publication since—are two smaller panels that the artists devised in tandem with the main composition. These are located at the far left above and below a balcony that interrupts the central space. At the top, an elderly man and woman mourn a dead youth in what appears to be a hybrid Lamentation scene; below, a strangely polemical still life features a broken colossal head, a drawing of torture, and other curious and sinister non-Mexican elements. Analyzing the relationship of these subsidiary scenes to the main action is crucial to understanding the Morelia mural’s multilayered meanings, both implicit and explicit.

(fig. 2) Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and Jules Langsner (left to right, standing without hats) with Mexican friends in Santa Maria, near Morelia, Mexico, 1934. Photo, David McKee Gallery, New York

It is evident to present-day viewers of the mural, as it must have been to Time‘s readers during the height of the Depression, that its young painters (fig. 2) worked hard to summarize a worldwide historical legacy of cruelty, prejudice, and malefaction. What is not as immediately obvious, perhaps, is how a specific confluence of insecurity, persecution, and violence, a topos of Mexico equal in intensity to its natural beauty, is ingeniously signified. Deeply encoded in the mural’s iconography of evil and pain are distinct clues, triggered by their understanding of Mexican alterity, to the artists’ own sense of “otherness” and profound desire to redress racial inequities. Referenced in particular is their shared relation to a heritage of Jewish persecution and ethical commitment.

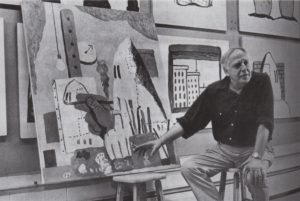

Since Phillip Goldstein was prob-ably primarily responsible for devising the fresco’s key imagery and dictating its rhetorical tone, a study of identity politics in The Struggle against Terrorism may prove especially significant in understanding this young artist’s further accomplishments. It was not long after his Mexican experience that Goldstein became Philip Guston, now celebrated as the abstract expressionist whose later turn to a sardonic, cartoonlike figurative style became so influential for postmodernist developments (fig. 3). (For the sake of simplicity, his more recognized name will be used throughout much of this essay.) Many art historians and critics writing about Guston’s distinguished career have dismissed the Mexican fresco (which the artist forswore until the 1970s) as mere juvenilia, seeing in its hyperrealistic Italianate imagery a disaffection on his and Kadish’s part with youthfully romantic notions about Mexican art and society. Scholars have never adequately recognized that the central premises of its sprawling theatrical design were, in fact, firmly rooted in both local and global events as well as in the painters’ personal histories. Echoes of this Morelian experience would reverberate throughout their respective oeuvres.

(fig 3.) Philip Guston with The Studio, 1969. Photo, Frank Lloyd / David McKee Gallery, New York

Back home, the extreme leftist politics of Guston and Kadish had already made their art a target for violent hate groups. After one particularly disturbing incident, they decamped for Mexico with their friend and “assistant.” Described by Time as an “itinerant poet,” Jules Langsner took charge of such menial tasks as mixing paint as well as promot-ing the Morelia mural’s story to the press; he would later become a distinguished West Coast curator and art critic. The journey to creative maturity for all three men was complicated. While almost completely unknown today, their 180-day sojourn in Morelia was a significant intermediate destination. This, we shall see, was particularly true for Guston.

Beginnings

As American expatriate Anita Brenner so vividly described in her book Idols behind Altars, the “persistence of ancient instincts and motivations” has always

been an important determinant of social, political, and cultural life in Mexico. A reverence for ritual and a fascination with terror and death, rooted in the country’s multilayered past, are resulting themes that scholars have explored. A further clue to Mexico’s concomitant private resonance for Guston, Kadish, and Langsner is provided in the analysis of noted intellectual Octavio Paz. In his book The Labyrinth of Solitude, Paz contends that insecurity and “otherness” based on mestizaje (race mixing) have had a strong psychological impact on his homeland’s national character. Many experts consider this collective sense of otherness a primary determinant of Mexican culture. Langsner’s later confession that he and his friends could “integrate with strands of other cultures probably as much in our bones as American peculiarities” intimates their understanding of Mexican alterity and suggests its effect on them.3 Given their immigrant backgrounds, these young artists would have approached their Mexican experience with a particular brand of “double consciousness.”

(fig. 4) Samuel and Reuben Kadish, ca. 1915. Photo by C. Gorman

from the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, with permission of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Three decades before the unveiling of The Struggle against Terrorism as celebrated in Time, the families of these three “angry young men” who left Los Angeles in 1934 to try their luck in an exotic land had also fled their homes, escaping anti-Jewish pogroms and other instances of race hatred and violence in the waning days of the Russian tsars.4 The Goldsteins departed Russia in 1905 in the wake of attacks by the Black Hundreds (antirevolutionary and anti-Semitic ruffians whose activities were unofficially sanctioned by the govern-ment) and the sailors’ mutiny aboard the battleship Potemkin in Odessa Harbor. Phillip (the original spelling) and Reuben were both born in 1913, Jules Langsner two years earlier. Reuben, whose father had been a Bundist in Kovno, moved from Chicago to Los Angeles with his family at age seven (fig. 4). By 1919 Phillip’s family (fig. 5) had also relo-cated there from the French-Canadian, Yiddish-speaking slums of Montreal. No birth certificate for the youngest of Rachel Goldstein’s seven children was ever issued. According to family gossip, Phillip’s real father may not have been his mother’s second husband, Lieb; the future artist was rumored to be the progeny of an affair in Odessa. Haunted by the feeling that Odessa was his “true” birthplace, Phillip was raised in New World ghettos on scary stories about his terrified family hiding from marauding Cossacks in Old World cellars.5

(fig. 5) Phillip Goldstein, at left, with his mother Rachel, brother Nat, sister Rose, and brother Irving in Los Angeles, early 1920s. Photo © Estate of Philip Guston, David McKee Gallery, New York

Whereas Kadish’s father, Samuel, a blue-collar worker, became active in causes for political and social justice in Los Angeles, Lieb Goldstein (also known as Wolf or Lewis) could never adapt to life in America. A brooding and doubt-racked, depressive man, he had worked in Montreal as a machinist for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Unable to find similar employment in the United States, Lieb was reduced to plying the slums of Los Angeles in a horse-drawn wagon picking up and reselling refuse. It was in either 1923 or the following year that Phillip discovered his father hanging from a noose slipped over the rafters of an outbuilding by their house.

(fig. 6) Reuben Kadish, Untitled (Dr. Entozoan), ca. 1935. Oil and mixed media, 20 1/2 x 16 1/2 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation and purchased with funds provided by Mrs. James D. Macneil. Photo © 2006 Museum Associates / LACMA

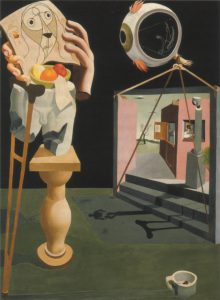

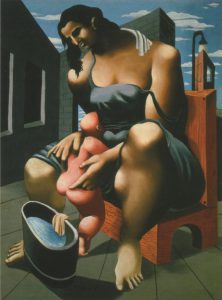

Phillip Goldstein and Reuben Kadish met in 1930 at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and, in an interesting side note, were teenage chums of Jackson Pollock. Reuben attested to his two buddies’ competitiveness. Imbued with the idea of seeking “a big life,” Jack and Phill, while at Riverside’s Manual Arts High, had worked at “living out a European fantasy.” Expelled together from Manual Arts for protesting funds wasted on athletics and ROTC (the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps), neither Pollock nor Guston would graduate.6 After less than a year at Otis, Guston dropped out, went to work for a radical Russian furrier, punched numbers on vests in a factory, drove a dry cleaner’s truck, and (capitalizing on his good looks and flair for the dramatic) played bit parts in Hollywood. Under the tutelage of local art guru Lorser Feitelson, he and Kadish discovered avant-garde painting. They focused their study on great masters of the past and present such as Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Max Ernst, and Giorgio de Chirico. They mixed these various influences—as seen in Kadish’s Untitled (Dr. Entozoan), completed after their return from Mexico (fig. 6), or Guston’s earlier canvas Mother and Child (fig. 7)—with cues from post-surrealism, most notably Feitelson’s melodramatic stylistic pastiche with strong film noir echoes (fig. 8).7

(fig. 7) Philip Guston, Mother and Child, 1930. Oil, 40 x 30 in. Private collection. Photo, David McKee Gallery, New York

For someone with no advanced formal education, Philip Guston was a highly literate adult; he was undoubtedly one of the most intellectually inclined of the abstract expressionists—certainly more so than Pollock. Writer Dore Ashton has noted Guston’s early fascination with James Joyce, Ezra Pound, E. E. Cummings, the French surrealists, California novelist Nathanael West (born Nathan Weinstein), and other authors “of the Left.” She mentions his later predilection for reading philosophy, especially that of Henri Bergson, Arthur Schopenhauer, Soren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Carl Jung, Thomas Aquinas, and the great Jewish thinkers Baruch Spinoza and Martin Buber. Guston’s special attraction to Franz Kafka has been well detailed; this developed furthest after he began teaching painting in the Midwest in the early 1940s. Kafka’s claustrophobic allegories of rootlessness and strange-ness wrought from his own tormented (Middle European) Jewishness were apparently easily absorbed into Guston’s own introspective and lugubrious (very Russian) feelings of victimhood inherited from his father.8

(fig. 8) Lorser Feitelson, Love: Eternal Recurrence, 1935-36. Oil, 54 1/4 x 66 V2 in. Phoenix Art Museum, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Lorenz Anderman. Photo, Craig Smith © Feitelson Arts Foundation, reproduced by permission

(fig. 9) Philip Guston, Conspirators, ca. 1930-32. Oil, 50 x 36 in. Unlocated © Estate of Philip Guston. Photo, David McKee Gallery, New York

In coming to terms with this Russianness, the writings of Isaac Babel provided Guston a pertinent model, more ironic and also more directly connected to Judaism than Kafka’s writings. The artist admired Babel’s short tales, many of which display a fervently as-similationist desire to escape ghetto life (the same life in the Pale of Settlement that had been led by Guston’s and Kadish’s forebears). Particularly relevant are Babel’s Red Cavalry Stories, based on observations made in 1920 when he disguised his identity to ride through Poland torching shtetls with General Budyonny’s Cossacks. These sketches have been characterized by literary scholars as saturated with their author’s unshakable love/hate relation to his upbringing “nailed to the Talmud.” Full of pathos, contradiction, and travesty, the Red Cavalry Stories display a fascination with the foibles of cruelty and violence for which Guston’s works, early and late, provide a close visual parallel. These range from Conspirators, a now-lost canvas from the early 1930s (fig. 9), to a 1977 painting dedicated “To I. B.” Babel’s writings obviously stoked Guston’s sense of displacement. As William Corbett, one of his many poet friends, so perceptively observed, “Babel, who could never be a Cossack and could not be a Jew while he rode with the Cossacks, fit Guston and the paradoxes in his artistic life perfectly.”9

I like Isaac Babel,” Guston himself pronounced in 1980, “because he deals totally with fact. There can be nothing more startling than a simple statement of fact, in a certain form. As Babel says, there’s no iron that can enter the heart like a period in the right place.” Annotating his recent paintings featuring the resurgence of (now more crudely drawn) white-hooded figures, Guston slipped a probable reference to both Conspirators and The Struggle against Terrorism into the following admission:

‘They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind the hood. In the new series of “hoods” my attempt was really not to illustrate, to do pictures of the Ku Klux Klan, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinates me, rather like Isaac Babel who had joined the Cossacks, lived with them, and written stories about them. I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan, to plot.’10

As social scientist Daniel Bell rightly observes, it is widely believed that a man is “first of all the son of his father.” But, disaffection from the anxious, parochial world of their immigrant parents was a hallmark of Jewish intellectuals of Guston and Kadish’s generation, and both eventually married non-Jews. In addition to masking his ethnic roots to placate the family of his Gentile wife, Guston’s name change likely served to put greater distance between himself and his unsuccessful father. Musa Mayer, Guston’s daughter, says she did not learn he had another name until she reached college; then she discovered that he had gone so far in his deception as to repaint his signature on at least one early work (Mother and Child). Yet, Mayer acknowledges, Guston felt deep ambivalence and increasing guilt over this rejection of self-hood. By the end of his life, he began to reembrace his heritage, writing, “I have never been able to escape my family…. Nothing has changed in all this time. It is still a struggle to be hidden and feel strange.”‘ 11 Philip Guston’s quest to un-derstand the forces that made him who he was took its earliest convincing artistic shape in an unlikely place. To understand what happened in Morelia, it is first necessary to go back to Los Angeles and examine Guston’s formative experiences with Kadish.

Los Angeles

Like Mexico but for different reasons, the California environment in which Phillip Goldstein and Reuben Kadish grew up was marked by insecurity. Los Angeles had its own brand of restiveness based on the unusual mobility, heterogeneity, and impermanence of its population. A city located “on the edge of America,” Los Angeles was settled in 1781 by the Spanish. Its picture-perfect weather, pseudo-Mexican architecture, and key industry, the movies, placed primary emphasis on superficiality and disposability. By the 1920s an accentuated need for reinvention and self-validation propelled many Angelenos into eccentric fads and occult activities. Some sought an exaggerated normality, adopting para-noid and exclusionary right-wing social behaviors to achieve it. An alarming number of violent hate groups flourished in depression-era Los Angeles. Targeting vagrancy, illegal aliens, Bolshevism, union suppression, and strikes, bullying police and vigilantes regularly violated the civil rights of local citizens. Night-riding goons with hoods, nooses, and burning crosses instead of swords and sabers terrorized targeted constituencies with the tacit or outright approval of the government.12 As indicated by Guston’s earliest extant works created between 1930 and 1933, such polarities of repression were unfortunately a familiar occurrence.

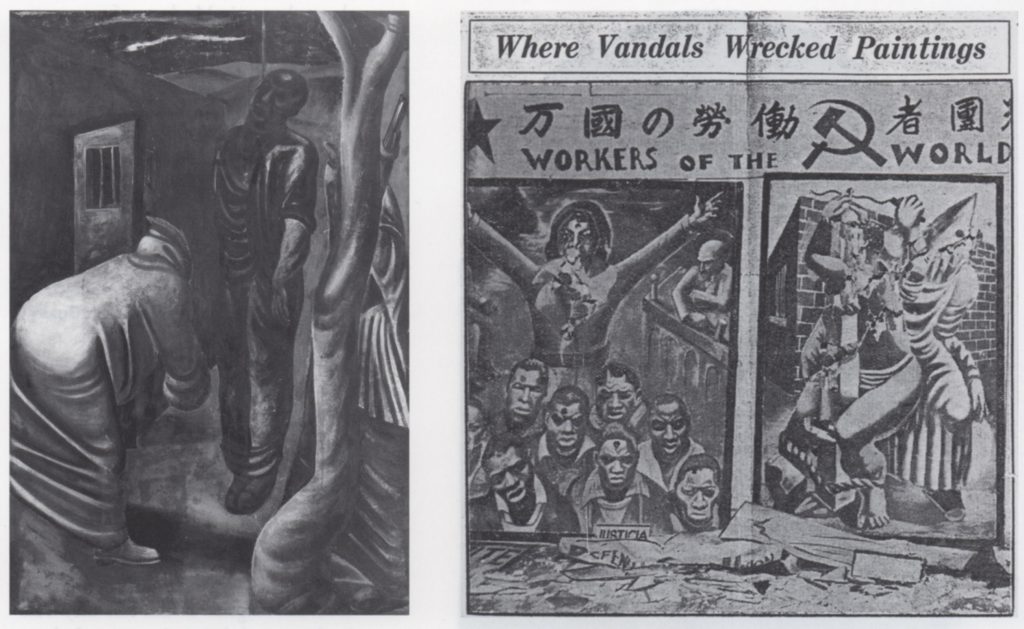

Every account of the careers of Guston and Kadish features the events of February 12, 1933, when Captain William F. Hynes of the Los Angeles Police Department’s notorious Red Squad and his American Legion posse destroyed portable murals the two artists had helped to create for the Hollywood branch of the Communist-affiliated John Reed Clubs. Harold Lehman, Murray Hantman, Luis Arenal (brother-in-law of Siqueiros), and other politically committed young artists were also participating in the proposed exhibition Negro America, meant to protest the trumped-up arrest and multiple convic-tions for rape of the Alabama Scottsboro boys—widely considered a “legal lynching.”13 The small frescoes for this show, painted on cement by Guston, Kadish, and friends, featured brutally honest, if somewhat aesthetically unsophisticated, images deploring the recent increase in the United States of atrocities against African Americans. Among the situations pictured were a black man hanging from a tree (fig. 10), the whipping of an African American by a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and a rapt white audience awaiting the imminent demise of a “boy” tied to a stake while flames licked at his feet. Hantman displayed portraits of the Scottsboro defendants under a banner advocating their freedom, an important agenda item of the American Communist Party, which sponsored the John Reed Clubs nationwide.14

(fig. 10 – left )Reuben Kadish, Portable mural for Negro America, Hollywood John Reed Club, 1933. Destroyed fresco, dimensions unknown. Photo from the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, with permission of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation, (fig. 11 – right) “Where Vandals Wrecked Paintings,” Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News, February 13, 1933. Photograph shows damaged frescoes for Negro America by Murray Hantman and Phillip Goldstein

Although the Los Angeles papers went further than Time by describing the pair as “decidedly ‘Red'” and not just “parlor pink,” Guston and Kadish were somewhat naive Marxists and never card-carrying members of the party. They did gravitate into its orbit, however, after demoralizing encounters with, as Langsner put it, “rapacious, dishonest and backwards” persecutory tactics. Guston was exposed to Klan rallies and abusive strike-busting after he left Otis and had to make a living. Police raided and ransacked the Kadish family apartment in 1928, throwing out possessions and destroying books, no doubt because of Samuel’s associations with Bolshevik sympathizers in Los Angeles, and Reuben observed a cross burning in the yard of a Jewish tailor who lived in Santa Monica. He and Guston watched in horror as sympathetic depictions of black Americans they and their cohort had painted on the Reed Club panels were bashed with lead pipes and rifle butts; Guston later recalled the eyes and genitals being pierced by bullets (fig. 11). They were dubbed “misguided individuals” in the press, and when they went to court over the incident a reactionary judge dismissed their case.15

(fig. 12) Piero della Francesca, Madonna della Misericordia, ca. 1445-60. Central panel of a polyptych, 4 h. 4 in. x 2 ft.11 3/4 in. Figure with “inquisitional hood” is second from left. Pinacoteca Comunale, Borgo Sansepolcro, Italy. Photo, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, New York

Guston’s portable fresco for Negro America was not his first presentation of a Ku Klux Klan plot. Violence had broken out in 1930 in the manufacturing plant in which he worked. Although not an eyewitness, as Ashton has described, Guston learned while an adolescent of the role played by the KKK and such right-wing associations as the American Legion in clearing Los Angeles of unions. In his first solo exhibition, held at the Stanley Rose Bookshop in 1933, he addressed these concerns, already interweaving public events and autobiography. A number of works shown there featured ropes and hangings; recall that it was Phillip who, as a boy, found his dead father and cut down the noose. Much later, Guston admitted to a fixation beginning at that time on the “kneeling figure with inquisitional hood” seen in Italian Renaissance paintings (fig. 12). “This medieval inquisition hat,” he wrote, “ignited something in me.” Although the lost canvas Conspirators, which was sold at the Rose Bookshop show, and a still-extant drawing with a similar topic have generally been dated about 1930, their shared themes suggest creation closer to the time of the aborted Hollywood John Reed Club exhibition.’16

In view of the aggressive thematic program of The Struxle against Terrorism, it seems plausible to read Guston’s Conspirators images, his and Kadish’s savagely mutilated Scottsboro portable compositions, and his obsessive return in the late 1960s to Klan-related subjects (in which, the artist admitted, he was “going back to my beginnings again”) as accommodating multiple layers of intertwined personal and political significance. On a personal level, Guston’s lifelong desire to orchestrate “living indictments” apparently stemmed from deeply embedded emotional roots. On a more public front, the importance of the John Reed Clubs as a depression-era forum for the articulation of minority opinion was noted by, among others, dealer Herman Baron, who donated space in Manhattan for a group exhibition similar to Negro America (this one entitled Struggle for Negro Rights). “Generally,” Baron observed, “unpopular minority voices [speak] for the conscience of the people and the freer that minority voices are heard the more conscience there is in the nation.” D. W. Griffith’s incendiary film Birth of a Nation (revived in a talking version in 1930) has been described as making the Klan’s belief in an “‘alliance of degeneracy’ between Jews and blacks visually explicit” in this era.17

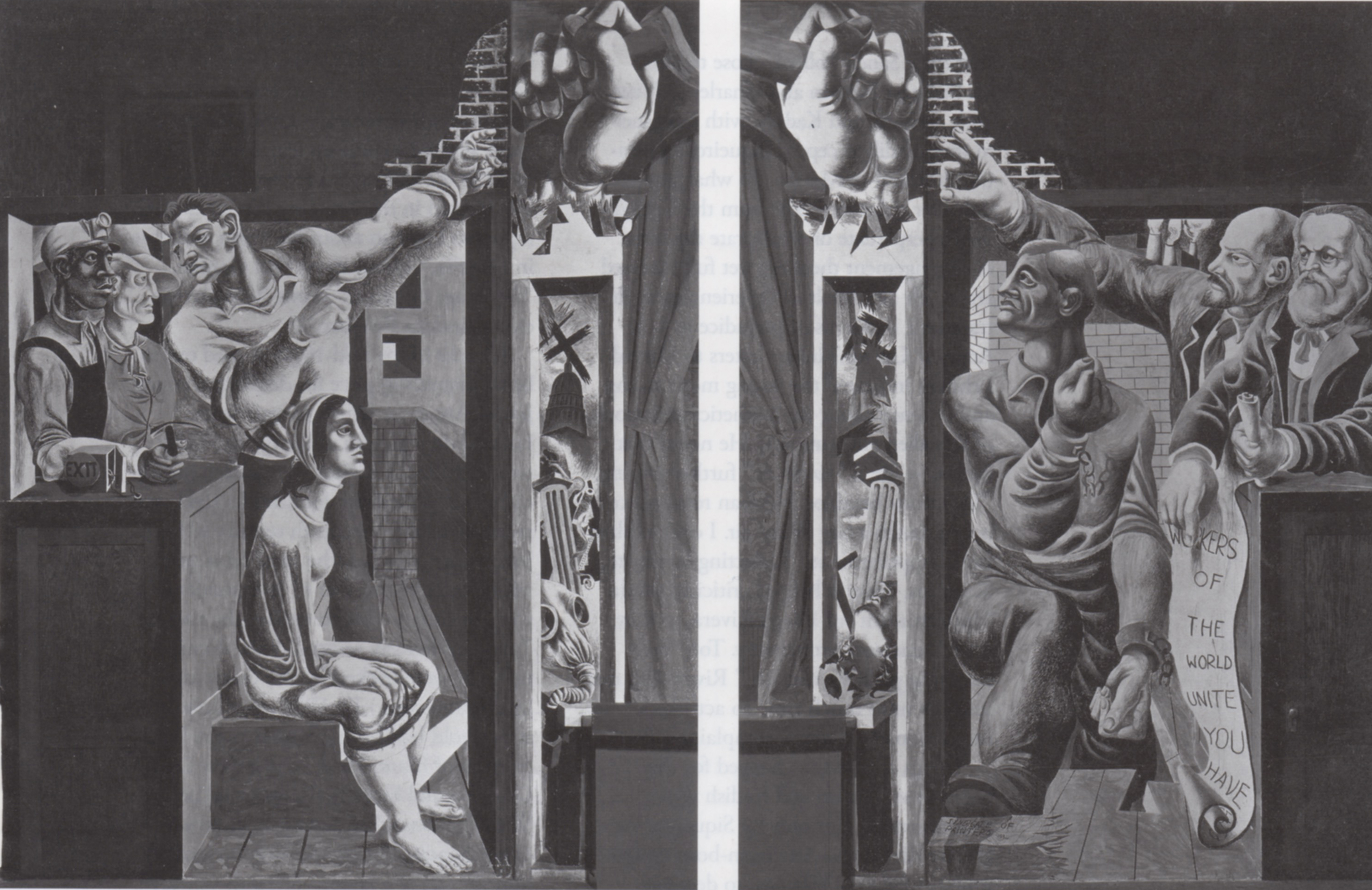

Between the time their Scottsboro panels were destroyed and they painted the much more ambitious Morelia fresco, Guston and Kadish assisted Hantman on a Public Works Administration project at the Frank Wiggins Trade School. More important, in early 1934 they created another mural—completely unknown today—for the proscenium arch of the Workers Alliance Center stage in downtown Los Angeles. In this case they were in charge and their assistant was Jackson Pollock’s older brother Sanford (later known as Sande McCoy). When a set of installation photographs of this project, which was created in twenty-one days and signed merely “Syndicate of Painters” (fig. 13), was sent to Siqueiros in Mexico, he promised to help any of its artists who wished to travel to his country to secure a commission.

The Workers Alliance Center mural was strongly influenced by Siqueiros’s 1932 Chouinard School fresco, The Workers’ Meeting(as well as another design by the Mexican created around that time for the auditorium of the Hollywood Reed Club), 18 but it also reflected themes made famous by Rivera and Orozco. Indeed, it likely constituted the most radically left-wing composition painted during the depression by American artists working in the United States. When Rivera had included the face of Lenin at Rockefeller Center the year before, his mural was destroyed.

(fig. 13) Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish, and Sanford Pollock, Mural for Proscenium, Workers Alliance Center, Los Angeles, 1934. Fresco. Photo from the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, with permission of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

As extant photographs indicate, the right-hand side of the design by Kadish, Guston, and Sanford Pollock featured Marx and Lenin, one of whom gestures toward two huge fists gripping Soviet symbols while the other points to a scroll displaying the initial phrase of the Communist Manifesto. A worker who has broken his shackles provides the foil to a kerchiefed female, a black miner, and two additional white members of the proletariat depicted at far left. One, a muscular youth, harangues the others to recognize the power of the party. Antiwar scenes and symbols glimpsed through two vertical openings prefigure the more imaginative and explicitly anti-Fascist iconography of The Struggle against Terrorism.

While little is known about the circumstances of the fresco commission at the Workers Alliance Center (except that Samuel Kadish, a professional wood grainer, worked on the building), its propagandistic fervor indicates that left-wing politics were more critical in the artistic educations of Reuben Kadish and Philip Guston than have heretofore been acknowledged. That they were mo-tivated and empowered to elaborate this subject in 1930s Los Angeles suggests, moreover, a need for further research and revision of the accepted history of early-twentieth-century West Coast art’s. 19

Mexico

Although Sande Pollock chose to join his brothers Jackson and Charles in New

York, Guston and Kadish, with Langsner in tow, readily accepted Siqueiros’s invitation to travel to Mexico. To what extent did their voluntary exile from the United States perpetuate or ameliorate the sense of estrangement these not yet fully formed artists felt as a result of experiencing such traumatic incidents of prejudice in Los Angeles? Guston’s initial letters to Harold Lehman indicated the young men’s strong ambivalence about the aesthetics and mores of this alien environment. He noted that their new life is “no cinch,” further griping, “The much heralded Mexican renaissance is very much a bag of hot air. I can’t explain my disappointment.” Reflecting loyalty to Siqueiros, Guston heaped criticism on the “opportunism” of Diego Rivera, at that time Siqueiros’s archenemy. Too “busy receiving gushing tourists,” Rivera did not seem to have much time to act like a true revolutionary, Guston complained.20

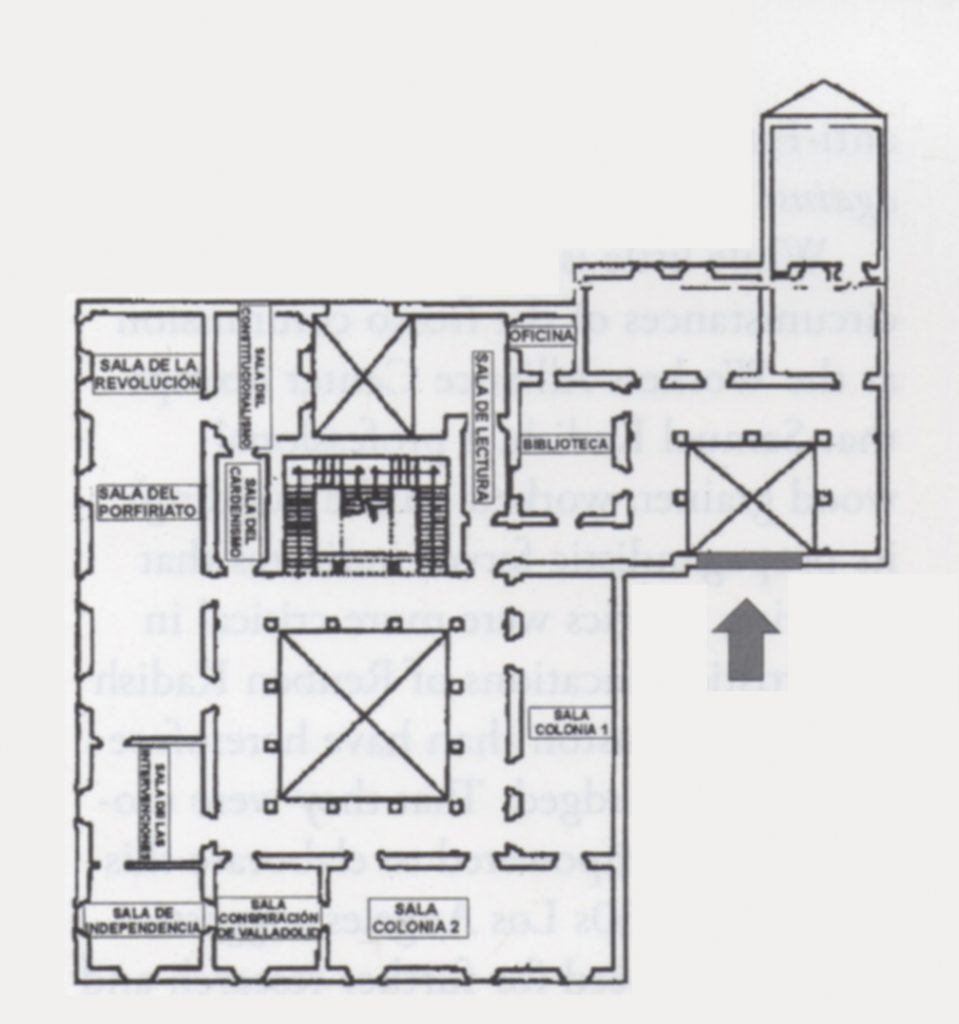

(fig. 14) Plan of Museo Regional Michoacan, second level

Things apparently changed for the better after Guston and Kadish were recommended, not only by Siqueiros but also by Rivera and American-born emigre muralist Pablo O’Higgins, to decorate an interior patio (fig. 14) of the imposing edifice in Michoacan where the doomed Maximilian—the Austrian emperor of Mexico under the auspices of the French in the 1860s—and Empress Carlotta had briefly sojourned in 1864. The building was now being run by the University of St. Nicholas of Hidalgo, a progressive religious institution, and used primarily as a state museum. Guston, with his better Spanish, left Mexico City first to negotiate with local art commissar Rodolfo Ayala as well as with Gustavo Corona, the college’s socialist-leaning rector. Corona had previously commissioned murals from three American women: the sisters Marian and Grace Greenwood and Ryah Ludins. (Grace Greenwood’s 1934 composition, Modern Industry, is located in the Museo Michoacano’s foyer leading into the patio space allotted to Guston and Kadish. Up to 1939 the university’s rectory offices were also located in this building.) In an excited report to Lehman about his warm welcome in Morelia, Guston wrote that Corona, “the image of Lenin,” wants “to make his city a modern Florence.”21

Morelia in the mid-1930s turned out to be an interesting place for disaffected young Jewish American leftists to experience. Located on a plateau of the Sierra Madre west of Mexico’s capital, the Spanish provin-cial city of Valladolid, founded in 1541, was renamed in the nineteenth century to honor Jose Maria Morelos, the local rebel priest whose feats in the War of Independence were legendary. (Much earlier, the native Tarascans fiercely resisted Aztec domina-tion but were tricked by the Europeans into submission.) By 1928 this Catholic stronghold had been adopted as the head-quarters of future Mexican president Lázaro Cardenas and his radical anticlerical party With Cardenas then serving as governor of Michoacan, the city of Morelia, located near the site of a famous fifteenth-century Inquisition trial, was transformed into a center of Cardenista insurgency at war with more conservative religious factions dominant in the region. The renegade Cardenistas opposed the “numbing effect” of Catholic fanaticism on the subsistence farmworkers known as campesinos, rejected racial stereotypes that marginalized native populations, promoted the syndical organization of the proletariat, and endorsed the collective benefits of culture. Portraits executed by Guston and Kadish in Morelia to make extra money indicate that the artists soon were on familiar terms with some of these local politicians (fig. 15).22 During a lull in the mural’s execution, the two, plus Langsner, were even given free train passes to attend Cardenas’s December 1934 presidential inauguration in Mexico City.

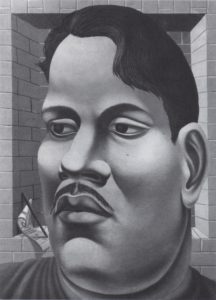

(fig. 15) Philip Guston, Portrait of Manuel Moreno Sanchez, 1934. Oil, approx. 4 ft. high. Unlocated. Photo courtesy of Musa Mayer

The announcement in Time magazine of the unveiling of Guston and Kadish’s mural after less than six months’ gestation was both hyperbolic and somewhat patronizing: “In that hot little place,” Time’s reviewer wrote, “black-coated government employees and peasants in straw sombreros gazed in open-mouthed wonder at one of the biggest, most effective frescoes in all Mexico.” Improbably, it was explained, this wall painting by inexperienced Americans would now provide Mexican schoolboys with “one more reason for being conscious of Morelia,” home to heroes of Mexican independence. But Time’s author had assuredly never seen the actual work, drawing inferences solely from information provided by Langsner. Local reaction is probably better judged by examining Benjamin Molina’s three-part review appearing sequentially in La Atalaya, a regional publication, on February 1, February 16, and March 1, 1935. The specificity of his text indicates that Molina had ample op-portunity to appraise firsthand the mural’s distinctive effects. (He may indeed have been one of the Mexicans who helped execute the painting.)23

Describing Goldstein and Kadish as “two youths that belong to this generation and follow its tendencies,” Molina focused his praise on their resolution of the design dilemma presented by the configuration of the museum patio walls. As Molina carefully explains, the mural’s surface spans two stories, including extensions above and below a balcony that cuts into the space. As a result, the observer’s viewing angle is deformed from all possible positions. This dis-tortion is especially prominent at the second level, where a banister abruptly interrupts the central portion. Molina heaps praise on the canny way the mural’s painters figured out how to accommodate the awkward physical and thematic transitions required to unify spatial and temporal disjunctions. They solved this, he relates, by introducing a severely foreshortened eighteen-foot-high male nude whose muscular arms, wrapped head, and thorax break the picture plane and whose equipoise is being shattered by men on ladders above attacking him with torture sticks (fig. 16). (Although not mentioned, Guston and Kadish also cleverly made use of a lightning rod cord attached to the wall at the right edge to indicate another victim of terror murdered by electrocution.) Not surprisingly, considering the locale of the artists’ upbringing, the kinesthetic impression produced by their hurtling giant—whose back-ward fall can be reexperienced from many points of view—seems closely linked to cinematography.24

(fig. 16) Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish (and Jules Langsner), The Struggle against Terrorism, 1934-35. Detail of falling man from central panel. Photo, Ellen Landau

Even more remarkable, the velocity of the monumental figure’s dislocation evidences conclusively Guston and Kadish’s astute understanding of the implications of polyangularity, a brand-new perspectival concept Siqueiros had devised after learning to use a movie camera in the United States. Guston’s letters to Lehman provide a worshipful description of photographs he and Kadish were sent of nudes Siqueiros had just finished paint-ing in Argentina, which, as he explains, are “very distorted so that they would appear not distorted because of the peculiar shape of the wall.” Guston tells Lehman that “as the spectator moves, [Siqueiros’s] figures move and rotate with him” (fig. 17).25 His own vertiginous version of Siqueiros’s advanced plastic innovation, created in partnership with Kadish, confirms its psychological as well as optical potency—communicating anxiety in the guise of spatial energy.

(fig. 17) David Alfaro Siqueiros, Plastic Exer-cise, 1933. Spray gun and nitrocellu-lose pigments on cement, 656 sq. ft. Quinta Los Granados, Buenos Aires. © 2007 Artists Rights Society, New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City. Photo, Archivo Sala de Arte Publico Siqueiros, Mexico City

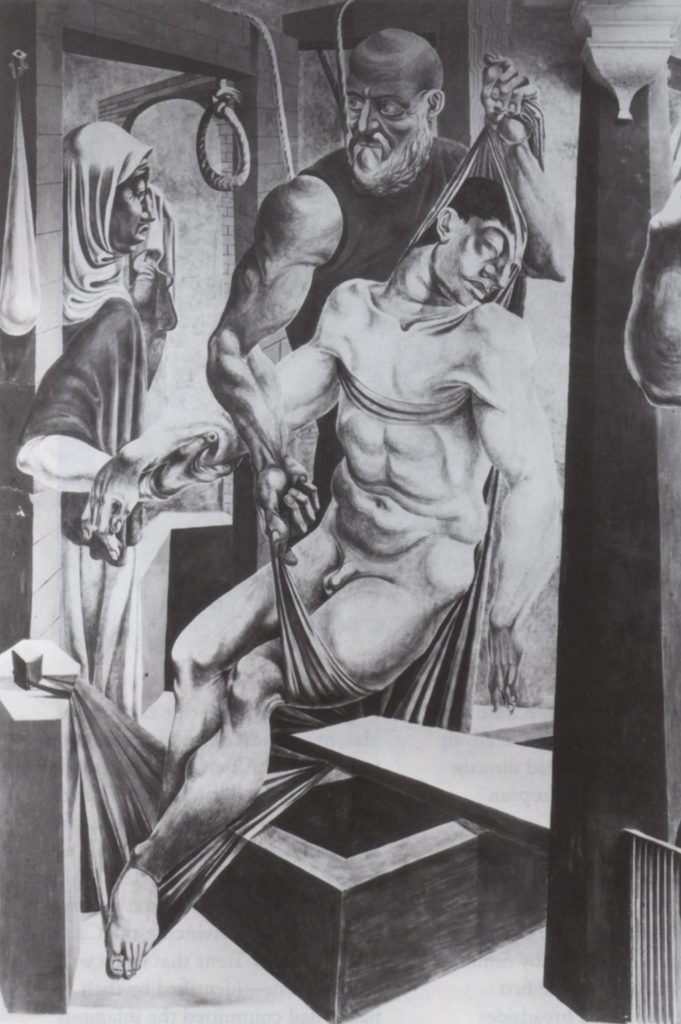

Glancing to the right and slightly above the catapulting giant (see frontispiece), visitors to the Museo Michoacano are drawn into a solemn and ritualistic tableau of equally frightening proportions, simultaneously conservative and innovative in narrative and form. Documentary evidence in Kadish’s papers indicates that the composite saga began at the extreme left, in one of the smaller spaces over the balcony.26 The scene of death and sorrow represented there, almost certainly by Guston, amalgamates traditional—especially Michelangelesque—Pieta, Deposition, and Lamentation imagery (fig. 18). It recalls his father’s suicide by hanging as well as the drawing he supposedly made at age seventeen, in which a black man being lynched by conspiratorial Klansmen is directly analogized with the martyrdom of Christ. While the facial features of the muscular corpse suspended over an empty, open tomb in Morelia may seem Meso-American at first glance, on closer examination a more conflated racial identity is discovered. Markedly Jewish in physiognomy, the profile of this tragic youth also bears Goldstein family traits; most prominent are Philip’s hooked nose and hooded eyes, physical similarities he shared with his older brother Nat, who died tragically at a young age (fig. 19).27

(fig. 18) Guston, Reuben Kadish (and Jules Langsner), Lamentation panel from The Struggle against Terrorism, 1934-35. Photo from the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, with per-mission of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

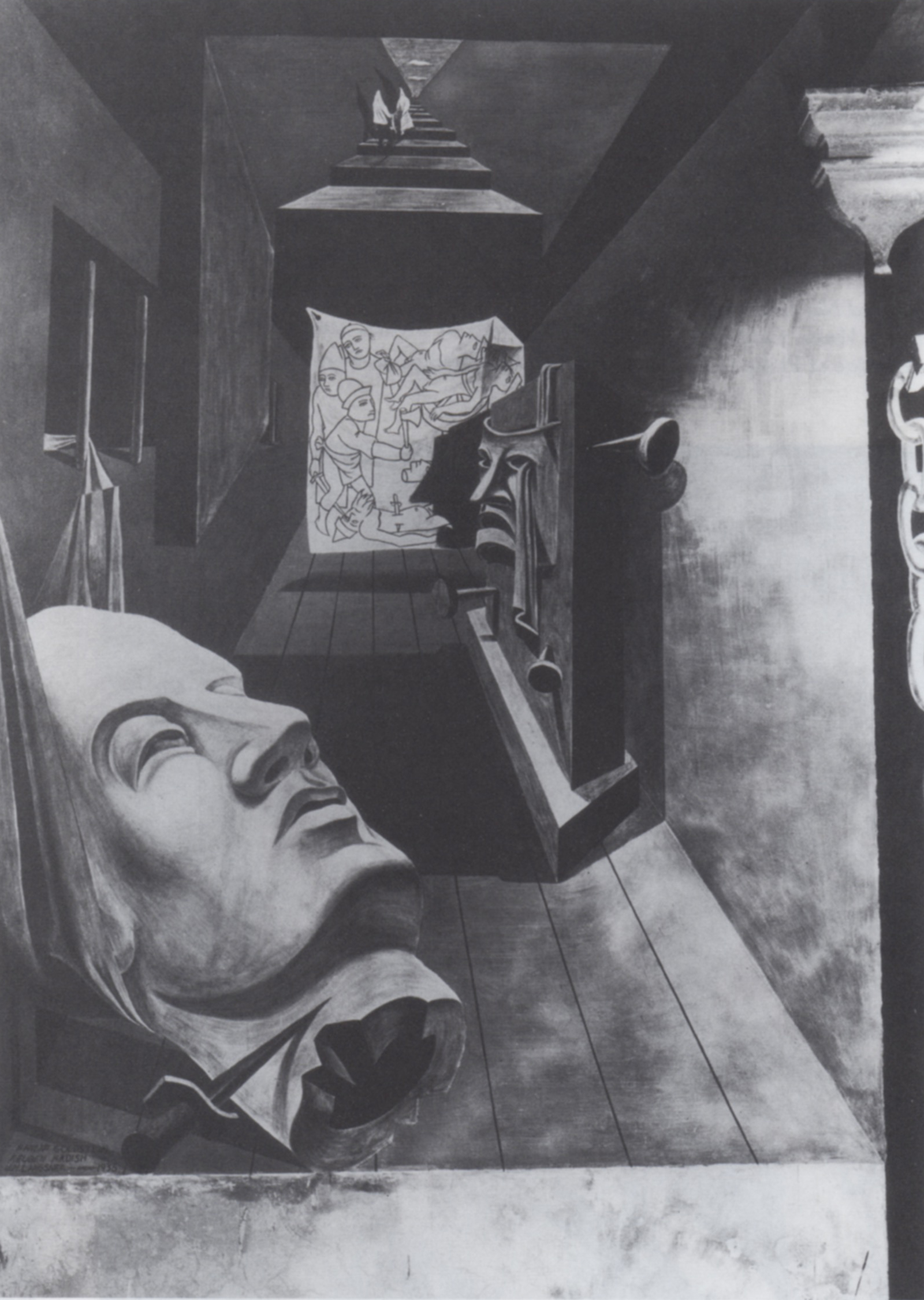

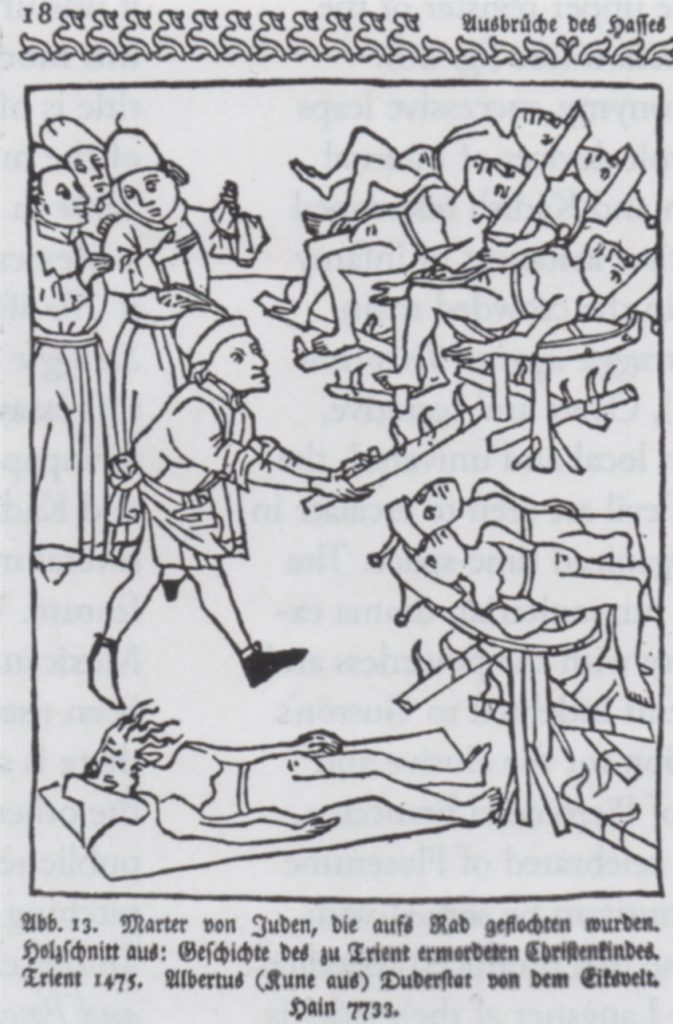

Installation photographs taken soon after the fresco in Morelia was completed, an item Langsner succeeded in placing in the Los Angeles Times, and a letter from Kadish in Mexico to Feitelson requesting instructions all indicate that the vignette located directly below this Lamentation scene was meant as a more pessimistic version of “subjective classicism,” one of the hallmarks of the California post-surrealist style. Even badly damaged by the leeching of saltpeter—which began almost immediately—this metaphysical still life a la de Chirico (one of the duo’s main artistic heroes) produces an eerie effect.28 Known from installation photographs donated to the Archives of American Art, its original composition (fig. 20) featured a fallen colossal sculptural head, which (like the Pieta figure above it) is supported in a sling of tightly drawn cloth. This was juxtaposed with a tearful mask of tragedy hanging from a nail attached to what looks like a wooden pain-inflicting contraption. Behind this, a tacked-up cartoon picturing yet another scene of torment was deftly inserted into the design. Although here viewers might plausibly surmise that a Hispanic codex provided a source or inspiration for this scene (as suggested by the Museo Michoacano’s former director), the grisly narrative Guston and Kadish deliberately chose to copy into this relatively inconspicuous space was instead directly based on an obscure 1475 European woodcut (fig. 21).29

(fig. 20) Guston, Reuben Kadish (and Jules Langsner), Post-surrealist still life panel from The Struggle against Terrorism, 1934-35. Photo from the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, with permission of the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

![(fig. 19) Phillip [top] and Nat Goldstein on the Beach in Venice, California, ca. 1929 © Estate of Philip Guston](https://reubenkadish.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/fig_19-185x300.jpg)

(fig. 19) Phillip [top] and Nat Goldstein on the Beach in Venice, California, ca. 1929 © Estate of Philip Guston

In view of the explicitly interrelated iconographic program of The Struggle against Terrorism, it is evident that Guston and Kadish (and, one presumes, Langsner) were aware of the fact that, during the Inquisition period, in Europe and in New Spain, hooded monks were enlisted as fanatical representatives of the Church Militant and sent out to harrow and oppress supposed blasphemers and heretics. Especially targeted in Mexico were judaizante, those accused of secretly practicing Jewish rites. In 1537 the Apostolic Inquisitor of New Spain publicly tried Gonzalo Gomez, an important political figure in Michoacan, as a suspected judaizer. Exactly how and when these three emigrant Angelenos had become familiar with an esoteric fifteenth-century leaflet created to stir up anti-Jewish sentiment in northern Italy will likely remain forever unknown. Although Kunne’s woodcut image, the Burning of the Jews of Trent, a copy of which is owned by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, seems to have been published only once before 1934 (in a 1903 German text), the artists appeared to know it intimately. That Guston and Kadish increased Kunne’s level of violence and affliction beyond the wheel and flame stick, depicting one of the Catholic torturers (also identified through distinctive headgear) as stabbing the dead elder Moses in the eye, indicates their advanced level of rage.31

(fig. 21) Albert Kunne (also known as Albertus Duderstadt von Eiksvelt) Burning of the Jews of Trent, 1475. Woodcut. Reproduced from Georg Hermann Theodor Liebe, Das Judentum in der deutscher Vergangenheit (1903), ill.13

The virtual line-for-line similarity of the tacked-up Morelia cartoon—today hardly visible—to Kunne’s design suggests that its injection into The Struggle against Terrorism was cathartic for these young American Jews. Since the Mexicans would likely not have understood such a reference, the Angelenos used—and accelerated—its horror to make a secret, individually meaningful statement. Accusations of Blood Libel had spurred the famous Kishinev pogrom a few years before their parents left the Pale of Settlement; the arrest of Mendel Beilis in 1911 (and his notorious trial in 1913) also caused an international scandal; and the Nazis were reviving this slanderous aspersion in the propaganda periodical Der Stfirmer at precisely the time Guston and Kadish were painting in Mexico. Additional accessories of persecution, many associated with tactics of the Gestapo as well as the Spanish Inquisition (these include chains, crosses, maces, nails, barred windows, ladders, flagellant whips, garrottes, and studded collars), were distributed by the artists throughout their Morelia composition. Recalling the symbolic use by Renaissance and baroque artists of the Anna Christi (the Instruments of the Passion such as the nails, scourge, and crown of thorns) and the frequent depiction in Catholic religious art of implements employed to persecute saints, the artists used to great effect the public and private connotations of this paraphernalia of pain and suffering. The timeliness of their message is underscored by the inclusion of two tiny figures in Ku Klux Klan regalia dragging a dead body up a set of wide stairs in the upper register of the post-surrealist section (see fig. 20).

Through metonymy, successive leaps in scale, and adroit devices of internal framing, Guston and Kadish telescoped and conflated other instances of infamy and corruption in the crowded main section of The Struggle against Terrorism (see frontispiece). Overt and secretive, present and past, local and universal, the consequences of evil are seen to escalate in a subjectively organized time-space. The result, a stylized humanitarian drama ex-pressing solidarity with the powerless and dispossessed, seems indebted to Guston’s lifelong admiration for the elusive and secretive world of Piero della Francesca, one of the most celebrated of Florentine painters, an enthusiasm he shared with Kadish. What the two produced together in Mexico (with Langsner at their side) is likewise dignified, strangely mute, elegiac, and—at certain key junctures—intensely and disturbingly phallic. The denouement of their chronicle, incorporated into an epic context of modern-day totalitarian symbology (a volumetric Nazi swastika as well as clenched Communist fists gripping hammer and sickle), provides a jarringly effective contemporary note. Borrowing Guston’s later characterization of the genius of Piero, it is obvious that the various thematic parts spread horizontally across the wall, as well as the psycho-logically redolent vertical layers of his and Kadish’s heroic Mexican work, “act on each other, repel and attract, absorb and enlarge one another” brilliantly.32

Aftermath

Conceptualized in a locale where postrevolutionary social policies were specifically aimed at erasing the historical stigma of torture and cruelty, Guston and Kadish’s 1934-35 Morelia fresco, often called The Struggle against War and Fascism in English-language accounts, has been known to the locals as La Inquisicion since it was uncovered in the early 1970s. While this more charged and morally indignant title is hinted at in Langsner’s description of the mural’s iconography published by Time in April 1935, the author of “On a Mexican Wall” misleadingly dubbed it The Workers’ Struggle for Liberty. The Struggle against Terrorism (adopted in this essay) was first used in a Los Angeles newspaper notice that announced Guston and Kadish’s newly finished composition several months before Time‘s lengthier feature. While indirectly referenced, the Mexican alternative appears never to have been used by the artists themselves, and there is some question as to how many of the other titles they (or Langsner, as their public relations agent) tried on for size in pitching the story in a variety of venues. To our ears today, The Struggle against War and Fascism seems too closely identified with standardized Popular Front rhetoric; it does not accurately indicate the more empathetic direction of the mural’s underlying themes. The Struggle against Terrorism, considered in context with local understandings of the painting’s inherently anti-papist tone, better articulates its overtly allegorical message and hints at its more deeply embedded, less public meanings. 33

After their Mexican experience, Kadish and Guston created another mural, The Physical Growth of Man, in Duarte, California. Then Kadish went solo on one of the most important WPA frescoes produced in that state, A Dissertation on Alchemy, painted in 1937 in San Francisco. But following his service in World War II, Kadish gave up painting to become a farmer. Many decades later, he turned to sculpture, and a considerable number of his mature works in three dimensions directly reflect the impact of Mexican style. How Guston’s formative experience in Morelia likewise played a crucial role in the accomplishments of his subsequent career is a somewhat more complicated topic, which requires preliminary recognition of the interdependence of personal authenticity and collective memory that helps define Jewishness. It turns on the notion, so well described by French theorist and philosopher Alain Finkielkraut, that an “eternal, invisible and ineffaceable” difference—one that collectively accommodates the respective lows and highs of outcast status plus greater ethical commitment—is integral to being Jewish.34

A clear awareness of this kind of ethnic inevitability undergirds two important critical judgments of Guston’s unusual artistic trajectory. These assessments were made by avant-garde composer Morton Feldman and poet and novelist Ross Feld, both of whom knew their subject well. While cited repeatedly in the Guston literature, Feldman’s and Feld’s observations have not yet been fully connected to the artist’s works and thinking process. Writing at the apogee of abstraction in both painting and music, Feldman’s comment in Art News Annual of 1966 that “Guston is of the Renaissance” probably struck its readers as a bewildering statement. Why would the composer make such a cryptic and patently ahistoric appraisal, one that could have seemed unflattering in his avant-garde context?

Naming as accessory one of the most admired painters of the Italian fifteenth century, Feldman offered the following imaginative explanation: “Instead of being allowed to study with Giorgione,” he writes, Guston “observed it all from the ghetto—in the Marshes outside Venice where the old iron works were,” adding significantly, “I know he was there.” Due to “circumstances” Feldman felt he had no need to define, Guston “brought that art into the diaspora with him.” Along with his final estimate of Guston’s oeuvre (“the most peculiar history lesson we have ever had”), Feldman’s deliberate choice of the charged terms “ghetto” and “diaspora’-determining facets of Jewish identity—indicates a frank recognition of his friend’s artistic impetus as directly reflecting the trope of marginality Finkielkraut defined. Indeed, as early as The Struggle against Terrorism, the ineluctability of Guston’s ethnicity appears to have been crucial to his interconnected psychic and artistic preoccupations. And, just as Finkielkraut admitted of himself, it might be inferred from the artist’s paintings and writings that “at every moment” he “sense[d] the coming thunder of the apocalypse.”35

What then should be made of the apparent commitment to nonobjectivity in Guston’s compositions of the 1950s and early 1960s, consisting of centralized, disembodied paint strokes, that established his preeminent position in the New York School? Here Feld’s opinion bears repeti-tion. “The more I saw of the work that was coming from Guston in the late [19[70s,” Feld once explained, “the more persuaded I became that he had only seemed to be an abstractionist during his earlier decades.” Instead, Feld surmised provocatively, “like a Marrano, a converso, like the under-ground Jews of the Spanish Inquisition [Guston had] been a secret image maker all along, coerced into abstraction but never grounded there, outwardly observing but also innerly undermining its rituals.” (A converso was a Spanish or Portuguese Jew who publicly converted to Christianity in the late Middle Ages to avoid persecution, while often continuing to practice Judaism in secret).36

(fig. 22) Philip Guston, at left, Reuben Kadish, and Jules Langsner with The Struggle. against Terrorism. Detail of 1935 photograph, prob-. ably by Casa Lopez Articulos Fotograficos Revelado Impresion y Amplification, Morelia. Photo, the Reuben Kadish Art Foundation

Confessing that he was “tired of all that purity” and desperately wanting “to tell stories,” Guston shed his converso persona once and for all by 1969 and returned resoundingly to figuration. His explanation of this change to Dore Ashton is crucial. “Without going into details right now,” Guston told his biographer, “it feels like I am going back to my beginnings again—of why I wanted to paint and to see the images I could make. . . I don’t think anything is ever finished in a painter’s life. . . . Nothing is ever forgotten.” In 1978, writing from his studio in rural Woodstock, New York, Guston again fell back on left-wing politics as a way to identify and metaphorize his continuing feelings of alienation. “No one knows it,” he remarked to Feld, “but right here in the woods—I feel like Lenin or Trotsky—in Zurich plotting the revolution!—I say battlegrounds—Yes, the battle—conflict-now is showing—it’s all in the open now—we are in the arena—exposed.” Casting his spiritual lot with revolutionaries from his ancestral homeland (the latter, a Jew who concealed his ethnic-sounding name; the former rumored to be part-Jewish), Guston explained that he was “not prepared yet—until now” to win the battle for meaning.37

Reviewing the twists and turns of Philip Guston’s career, it appears more than evident that this “battle,” still in play so close to the end of his life, was the same one Phillip Goldstein had been waging from the start. In collaboration with Reuben Kadish, one of its first significant rounds was fired in Morelia (fig. 22). Whatever name it is given, their 1934-35 fresco in Mexico is far froman immature or inconsequential statement. Instead, it reveals a remarkably sure determination by idealistic young diaspora Jews to bear witness by inserting their own “postmemory” anxieties into a larger geopolitical matrix. Appropriating the historic Inquisition as catalyst, they orchestrated a pictorial structure imaginatively reflective of apprehensions and insecurities endemic to both Los Angeles and Mexico. Adding what W. E. B. Du Bois termed the “double consciousness” of the outsider, Guston and Kadish adroitly wove firsthand concerns into the global context of increasingly dangerous times. Masked behind a controlled and disquiet-ing ambiguity, their complex moral indictment is nothing short of astonishing in its depth and precocity.38

Notes

This article could not have been completed without the support of Musa Mayer, David McKee, and Judd Tully as well as David Areford, Anders Bergstrom, Carolyn Walker Bynum, Irene Herner, Jay Landau, Marilyn Lavin, Eugenio Mercado Lopez; Dan, Carol, Ruth, Morris, and the late Frank Kadish; Michael Morford, Leah Poller, Arlene Sievers, the late Kirk Varnedoe, and Froma Zeitlin. I also thank staff members at the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, Laura and Alvin Siegal College of Judaic Studies, and the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, where much of this essay was written.

1. The mural was started in August 1934 and completed by January 21, 1935,when the artists signed the Museo Michoacano visitors’ book and departed; author’s interview with Eugenio Mercado Lopez, former director, Museo Micho-acano, Morelia, Mexico, May 28, 1998. Handwritten information in the Reuben Kadish Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter AAA), confirms these dates and indicates that Arriaga, museum head in the 1940s, ordered the mural covered with coarse cotton cloth mounted on a frame. This was painted to gain more wall space for anthropological and historical exhibits and to protect the mural from destruction by radical religious groups such as the Cristeros. Tests performed in 2005 by conservators Maura Kelly and Krystal Saltmeyer indicate whitewash was applied directly over the fresco in at least some areas. Mercado Lopez con-jectures that the museum was unable to obtain from the archbishop a huge eighteenth-century painting depicting a key event in local religious history, El traslado de las monjas dominicas a su nuovo con-vento, until Guston and Kadish’s mural was removed from public view. The mural was rediscovered in the mid-1970s by workers trying to fix a humidity problem. Mercado Lopez, “La Inquisicion: Un mural del Museo Regional Michoacano de Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico,” July 2001; revised for Acento: Seminario de la Cu!tura, La Voz de Michoacan, year 11, no. 584 (May 12, 2004): 2-5.

2. For this and all subsequent quotes from Time, see “On a Mexican Wall,” Time, April 1, 1935, 46, 48.

3. See Anita Brenner, Idols behind Altars (New York: Payson & Clarke, 1929); Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Soli-tude: Lift and Thought in Mexico, trans. Lysander Kemp (New York: Grove Press, 1961). See also Roger Barton, The Cage of Melancholy: Identity and Metamorphosis in the Mexican Character (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1992); Samuel Ramos, Profile of Man and Culture in Mexico, trans. Peter G. Earle (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press); and Wallace Thompson, The Mexican Mind: A Study of National Psychology (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1922). For the quote, see Langsner to Kadish, March 30, 1938, Kadish Papers, AAA. For more on Langsner, see his obituary, Los Angeles Times, October 2, 1967; and biographi-

cal statements in the Jules Langsner Papers, AAA

4. Guston, Kadish, and Langsner were characterized as archetypal “angry young men” by painter Fletcher Martin in “Ret-rospective Notes about My Friendship with Philip,” typescript, Dore Ashton Papers, AAA.

5.For details of the artist’s childhood in this essay, see Musa Mayer, Night Studio:A Memoir of Philip Guston by His Daughter (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988). In Yes, but . . . : A Cultural Study of Philip Gaston (New York: Viking Press, 1976), Dore Ashton, purportedly at Guston’s behest, never states his birth name was Goldstein or describes his parents as Jewish but mentions friends includ-ing Kadish, “whose father had fled persecution after the Russian Revolution of 1905.” Given the Goldstein family’s date of emigration, rumors of the affair in Odessa seem implausible. For Reuben Kadish’s family background, see Frank Kadish, In Search of Samuel Kadish: A Genealogical Journey (Phoenix, Ariz.: privately published, ca. 1999), 3-5. Born Samuel Schuster on May 15, 1885, Kadish’s father was raised in Kovno, now in Lithuania.

6. Reuben Kadish, interview by author, May 2, 1979, New York City. For more on Pollock’s and Guston’s shared high school experience, see Ashton, Yes, but. . . , 13-15; Deborah Solomon, Jackson Pollock: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987), 37-43; and Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1989), 134-36. In letters Guston sent to Kadish as late as 1936-37 (Kadish Papers, AAA), he signs “Phill” with a double 1.

7. On post-surrealism, see Susan Ehrlich, ed., Pacific Dreams: Currents of Surrealism and Fantasy in California Art, 1934-1957 (Los Angeles: UCLA at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, 1995); and Michael Duncan, ed., Post Surrealism (Pasadena: Pasadena Museum of California Art, 2003). A letter Guston and Kadish sent Feitelson from Morelia on December 11, 1934, indicates their respect for him as an artist despite political disagreements; Lorser Feitelson Papers, AAA.

8. See Dore Ashton, “Parallel Worlds: Guston as Reader,” in Philip Gaston Ret-rospective, ed. Michael Auping (New York: Thames & Hudson with Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2003), 83-91. According to Guston’s former student and associate Stephen Greene, after watching films at the University of Iowa about concentration camps, “Much of our talk was about the holocaust and

how to allegorize it”; see Ashton, Yes, but . . . , 74.

9. William Corbett, Philip Guston’s Late Work: A Memoir (Cambridge, Mass.: Zoland Books, 1994), 45. Descriptions of Babel are from Harold Bloom, ed., Modern Critical Views: Isaac Babel (New York: Chelsea House, 1987).

10. For the first quote, see Mark Stevens, “A Talk with Philip Guston,” New Repub-lic 182 (March 15, 1980): 26. For the second, see “Philip Guston Talking,” transcript of a 1978 lecture; reprinted in Philip Gaston Paintings, 1969-1980, ed. Renee McKee (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1982), 52.

11. Daniel Bell, “Reflections on Jewish Iden-tity,” Commentary 31 (1961): 471, 476. On Guston’s possible motives in leaving behind the Goldstein name, see Mayer, Night Studio, 21-24, 228-29; and Corbett, Philip Guston’s Late Work, 60-61. For the Guston quote, see Mayer, 24.

12. See Paul Karlstrom, ed., On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950 (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1996). Articles decrying aber-rant right-wing behaviors on the West Coast include Herbert Klein and Carey McWilliams, “Cold Terror in Califor-nia,” Nation 161 (July 24, 1935): 97-98; and Lillian Symes, “California, There She Stands!” Harper Magazine 170 (February 1935): 366.

13. This installation predated by several years the better-known New York shows Struggle for Negro Rights and An Art Commentary on Lynching held in 1935. See Helen Langa, “Two Anti-Lynching Art Exhibitions: Politicized Viewpoints, Racial Perspectives, Gendered Constraints,” American Art 13 (Spring 1999): 10-39; and Dora Apel, Imagery of Lynching: Black Men, White Women and the Mob (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers Univ. Press, 2004), 83-132.

14. On the Scottsboro case, see James Goodman, Stories of Scottsboro (New York Vintage Books, Random House, 1994). Photos of some of the porta-ble murals meant for Negro America are included in the Kadish Papers, AAA, identified in Kadish’s handwrit-ing on the reverse side. They include

his composition of a lynched black man hanging from a tree with a white-robed figure bent before him (see fig. 10). Luis Arena’ depicted the black “boy” set aflame in front of a white audience. Lehman’s image of a shackled African American man kneeling before two columns, Analogy: Labor-Capital, is published in Laurance P. Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1989), 216. Hantman’s Free the Scottsboro Boys was illustrated in International Literature 3 (March 1935): 107.

15. For “decidedly ‘Red,'” see Arthur Millier, “Brushstrokes,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 1935, sec. 2, 10. Langsner’s quote is from a letter to Reuben Kadish, March 30, 1938, Kadish Papers, AAA. On the apartment raid, see Frank Kadish, In Search of Samuel Kadish, 8. Reuben Kadish spoke of the cross burning in an interview with James Oles, June 1991, cited in “Walls to Paint On: American Muralists in Mexico, 1933-1936,” PhD diss., Yale University, 1995, 330. He told Jeffrey Potter that on another occa-sion, “The papers wrote about us, saying we were ‘misguided individuals corn mining themselves to Communism'”; see To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biogra-phy of Jackson Pollock (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1985), 49.

16. Guston’s Stanley Rose exhibition was reviewed positively by Arthur Millier in “Two Pairs of Painters and Some Singles Offer Shows,” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1933, sec. 2, 5 (Ferdinand Perret Papers, AAA). Guston’s comments on the medieval inquisition hat are found in handwritten notes to Ashton dated June 1973, Ashton Papers, AAA.

17. Quote is from Herman Baron, “History of the A.C.A. Gallery,” handwritten notes, A.C.A. Gallery Papers, AAA. For quoted comment on the Klan and Jews, see Bram Dijkstra, American Expression-ism: Art and Social Change, 1920-1950 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Columbus Museum of Art, 2003), 138.

18. “On a Mexican Wall,” Time, 46, describes how one of the two Morelia artists (certainly Kadish) “had helped Siqueiros finish a fine fresco in the Workers’ Cultural Center in Los Angeles two years before,” a probable reference to the Reed Club auditorium. Oles states in “Walls to Paint On,” 332, that Kadish recalled images of the Klan in this composition.

19. The only published discussion of the destroyed Workers Alliance Center fresco is Arthur Mailer’s negative review, “Communists Incited to Stir Up Trouble through Artists’ Propaganda-Paintings,” Los Angeles Times, August 26, 1934, sec. 2, 1, 3 (Perret Papers, AAA).

20. Guston commented on Rivera in a July 14, 1934, letter to Lehman (Kadish Papers, AAA). For the three friends’ trip to Mexico in an old jalopy (information provided by Kadish to Ashton, March 9, 1973), see Ashton, Yes, but . . . , 30-31. For their experiences in Mexico before Morelia, see Oles, “Walls to Paint On,” 335-36. Kadish told Ashton there was “a little trouble” at the end of their stay: “Called up before governor [Benigno Serrato]. We came back to LA.” He told Oles they had to leave because of Langsner’s amorous dalliance with the wife of a Mexican official.

21. Details about the museum and uni-versity personnel are from Eugenio Mercado Lopez, “La Inquisicion,”2-5. See James Oles, “The Mexican Murals of Marian and Grace Greenwood,” in Out of Context: American Artists Abroad, ed. Laura Felleman Fattal and Carol Salus (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004), 113-34. In “Walls to Paint On,” 118-92, Oles discusses Ludins’s ill-fated mural in Morelia as well. Ludins wrote a memoir, “Painting Murals in Micho-acin,” Mexican Lifi, 11 (May 1935): 22-23. Guston’s quote is from a letter to Lehman, July 14, 1934 (Kadish Papers, AAA). Guston also writes of Mexico, “Here a painter is judged only by his political content, the other things (plastique, comp[osition] etc.) is [sic] not secondary, but unimportant! Some country.”

22. See Marjorie Becker, Setting the Virgin on Fire: Ldz.aro Cdrdenas, Michoacan Peasants, and the Redemption of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1995). In a letter to Lehman of October 4, 1934, Guston explains that, in two or three more plasterings, the mural will be half completed and notes he and Kadish are making other paintings on the side to earn money. One he sold to the local president of the P.N.R. (the Partido Nacional Revolucionario political parry), and he had recently finished a portrait of a local magistrate: “just a huge head four feet high. Plenty of fat on this boy, too.” At the same time, Kadish portrayed “a local playboy”; Guston adds, “We must live.”

23. Discussion is based on Benjamin Molina, “El Fresco de Kadish y Goldstein,” La Atalaya, year 1, February 16, 1935. I thank David McKee and Eugenio Mercado Lopez for access to the article and Jay Landau for translation. Mercado Lopez speculated on Molina’s role as assistant to the project in interview by author, May 1998; and in “La Inquisicion,”4. Based on his name, Molina may also have been Jewish.

24. An undated letter from Sande McCoy to Kadish likely refers to this element of the mural. McCoy writes: “The kinesthetic problem you are working on is an inter-esting one-more mural painters might do well to consider things of that nature when attacking a wall.” This was prob-ably written before October 4, 1934; on that date Guston tells Lehman, “Sandy [sic] wrote us from New York and says nobody there is doing the kind of stuff all of us arc doing.” Kadish Papers, AAA.

25. Guston letter to Lehman, July 14, 1924; the section describing Siqueiros’s Plastic Exercise is quoted in Ashton, Yes, but . . . , 31-32. For further discussion of this innovation and its influence on Guston and Kadish, see Irene Herner, Siqueiros, del paraiso a la utopia (Mexico City: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2004), 329-33. The bound female figure placed to the right of the hurtling giant was likely inspired by the plasticity of Siqueiros’s Proletarian Victim, a portable mural of 1933.

26. See handwritten diagram, labeled “Detail from Mural in Museo Michoacana, Morelia, Mich. Mexico 1934,” sent by Guston and Kadish to Los Angeles pho-tographer Floyd Faxon, along with an in situ photograph, Kadish Papers, AAA. The diagram shows that only the Lamentation scene over the balcony had been completed. In situ photos in Guston’s papers indicate both ends were painted before the middle.

27. Which artist was responsible for what sections of the mural remains an open question. In later years, as in Time, both professed not to recall. (After the 1930s, Guston did not acknowledge his participation until Ashton’s 1976 biography.) The upper right figures in Morelia carrying Communist symbols exhibit the more generalized forms characteristic of Kadish, while the deeply shaded, muscular Pieta figure and hurtling man rep-resent Guston’s typical style. A photo of Guston high up on a scaffold next to the hooded priest with dagger and book seems to confirm his responsibility for the Klan-related figures. Oles (“Walls to Paint On,” 343-44) asked Ashton and Francis V. O’Connor for their opinions. Both lean toward Kadish as responsible for structure, technique, and overall design, with Guston the probable primary initiator of specific iconographic concepts, and Iconcur. Nat Goldstein’s death from gangrene when he was in his 20s is recounted in Mayer, Night Studio, 17.

28. Kadish wrote to Feitelson on December 11,1934, requesting “some material on composition as applied to surrealism” in order to “introduce one section painted along surrealist concepts” (Feitelson Papers, AAA). Time’s reviewer opined, “Fortunately, Reuben Kadish and Phillip Goldstein took nothing but their technique from New Classicist Feitelson.” But the artists responded to Arthur Millier (“Time Magazine Errs,” Los Angeles Times, April 7, 1935), “Time ignored ‘the culminating panel of our fresco, done in this very New Classicist manner.'” I thank Roger Van Oosten for this source.

29. Although it is unclear who copied the cartoon, Kadish probably painted the fallen colossal head. Ralph Stackpole remarks in “Reuben Kadish,” California Arts and Architecture 58 (April 1941): 21, that Kadish had “some delight in the busted heads of Greek statues, appearing often crushed and shattered.” Mercado Lopez incorrectly describes the tacked-up cartoon as representing indigenous people being burned on the feet by Catholic priests.

30. For more on this case, see Medieval Justice: The Trial of the Jews of Trent (New York: Yeshiva Univ. Museum, 1989); and R. PoChia Hsia, Trent 1475: Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, in cooperation with Yeshiva Univ. Library, 1992). On Kunne’s woodcut images, see Eric Zafran, “The Iconography of AntiSemitism: A Study of the Representation of the Jews in the Visual Arts of Europe, 1400-1600,” (PhD diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1973); and Lamberto Donati, L’Inizio della stampa a Trento ed it Beato Simone (Trent: Collana Edizioni del Centro Culturale, 1968). I thank David Areford for suggesting the last source and Michael Morford for his translation.

31. For the Michoacan trial of Gonzalo Gomez, see Richard E. Greenleaf, The Mexican Inquisition of the Sixteenth Century (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1969), 45-73. Donati’s L’Inizio della stampa a Trento describes scene 11 of Kunne’s folio: “Seven Jews, accused for the death of Simon, were convicted by the court and were to be burned alive. The scene represents the execution. In the presence of three magistrates, they have been placed on wooden supports under which an executioner lights the fire. Moses, an old man of 80 years, died during the trial, but was also subjected to torture.” The only book in which scene 11 from Kunne’s 1475 Trent series was published before 1934 (and therefore Gaston and Kadish’s probable source) appears to be Georg Hermann Theodor Liebe, Das Judentum in der deutschen Vergangenheit (Leipzig: E. Diederichs, 1903).

32 Philip Gaston, “Piero della Francesca: The Impossibility of Painting,” Art News 64 (May 1965): 38-39. Elsewhere, Gaston declared his lifelong goal as the creation of paintings one could “read as one would read an Old Master” (undated notation, Ashton Papers, AAA). Guston’s praise of Piero’s complexity to Ashton in June 1973 also seems apropos. He wondered at “the mystery when you deal with forms in front of forms. Produced because something is being hidden. Like a deck of cards.”

33 It is unclear whether Langsner pro-vided Time’s title, The Workers’ Struggle for Liberty, or if the magazine’s writer derived it from Langsner’s description. Kadish, interview by Oles, 1991, “Walls to Paint On,” 334, confirmed Langsner’s role as public relations flack. Although Oles and Karen Cordero Reiman use The Struggle against War and Fascism in their South of the Border: Mexico in the Ameri-can Imagination, 1914-1947 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 198-201, Oles suggests the artists adopted that appellation retroactively in response to the Popular Front and states, in “Walls to Paint On,” 357, that he prefers Time’s title. In “Brushstrokes,” Millier used The Struggle against Terror-ism. On the Mexican title, sec Mercado Lopez, Acento, 2-5.

34 On the Duarte mural, see Francis V. O’Connor, “Philip Guston and Political Humanism,” in Art and Architecture in the Service of Politics, ed. Henry A. Millon and Linda Nochlin (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1978), 340-54; and Susanne Muchnic, “The Shock of the Old,” Los Angeles Times, June 7,1998. A Dissertation on Alchemy, painted for the San Francisco State College Science Hall and completed in August 1937, is illustrated and discussed in Stackpole, “Reuben Kadish,” 20-21; information on it is included in the Kadish Papers, AAA. See Main Finkielkraut, Le Juif imaginaire (Paris: Editions du Scull, 1980), trans. Kevin O’Neill and David Suchoff as The Imaginary Jew (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1994).

35 Morton Feldman, “Philip Guston: The Last Painter,” Art News Annual XXXI 1966 (October 1965): 99. For “coming thunder,” see Finkielkraut, Imaginary Jew, 7-8

36. Ross Feld, Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston (New York: Counterpoint, 2003), 83.

37. For “tired of all that purity,” see Mayer, Night Studio, 153. “Oh, it is all so circu-lar, isn’t it?” Gaston remarked to Ashton toward the end of his life. “The recent work makes me feel free to use whatever formal and plastic imagery and capabilities I may possess. I mean from my own past too—all the memories.” “Please forgive my immodest comparison,” he importuned, “but like Babel, I want to `paint’ of things long forgotten.” Letter of August 25,1974 (Ashton Papers, AAA), cited in Mayer, Night Studio, 12. Remark to Feld from a September 1978 letter, quoted in “Gaston in Time,” Arts Magazine 63 (November 1988): 43.

38. Discussing children of Holocaust survivors, Marianne Hirsch states, “Post-memory characterizes the experience of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are . . . shaped by traumatic events that can neither be understood nor recreated.” See Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photograph. Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1997), 22-23. Although in 1934-35 Gaston and Kadish could not have known the extent of Nazi persecution of the Jews, their parents’ experience with pogroms was a rehearsal for the Final Solution. Guston’s later fixation with the concentration camps (note 8) confirms his deep feelings about the World War II genocide of the Jews. The piled-up shoes and limbs featured in many of his late paintings have been interpreted in a Holocaust context. Double consciousness is a central theme of Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, first published in 1903.